Edzell Castle is a ruined 16th century castle which despite its frail shell, still stands proudly today within its own grounds on the outskirts of the small Angus village of Edzell, which in turn is approximately five miles north of the town of Brechin.

Historic Environment Scotland site: Edzell Castle

Visit Scotland site: Edzell

For many years, this sleepy village was best known for the air force base RAF Edzell which ceased operations a number of years ago.

What few people realise, including probably most locals, is that the old ruined castle houses a very interesting esoteric curiosity- a walled garden, which may have played host to a number of key players in the Rosicrucian revival in 17th century Scotland.

The first castle to be built at this location was a timber ‘motte and bailey’ construction, built to protect the mouth of Glenesk, which at the time was a strategic pass leading north into the Highlands of Scotland.

The ‘motte’ – or mound, is still visible today, situated about 980 feet south-west of the present castle, and dates from around the 12th century.

The castle was the seat of the Abbot, or Abbe family, and was the centre of the former village of Edzell of which no trace now remains.

The Abbot family were succeeded as Lords of Edzell by the Stirlings of Glenesk who were in turn followed by the Lindsay family.

In 1358 Sir Alexander De Lindsay, third son of David Lindsay of Crawford married Katherine Stirling, the heiress to that family.

Alexander’s son David inherited the title of Earl of Crawford in 1398.

In 1513, the castle and adjoining lands were inherited by another David Lindsay who was a descendent of the 3rd Earl of Crawford.

This David Lindsay opted to build himself a new house and erected a tower-house and courtyard in a more secluded and sheltered location near to the old castle.

He was given the title of Earl of Crawford in 1542, following the death of his cousin, the 8th Earl, who had disowned his son.

In around 1550 the Earl decided to expand the property by adding a west-range which included a new entrance gate and hall.

The 9th Earl’s son – also called David, was born in 1551, educated in Paris and Cambridge, and became a well-travelled man in continental Europe.

He never became the 10th Earl of Crawford owing to the fact his father returned the title to the senior branch of the family following the death of the 8th Earls’ wayward son; although he was subsequently honoured with a knighthood, becoming Sir David Lindsay, Lord of Edzell in 1581.

In 1593, he became a senior judge in Scotland and took the title of Lord Edzell in 1593; in 1598, he was appointed to the Privy Council. He retained the Edzell estates and carried out numerous improvements to it in his time there, including woodland planting.

He also engaged in mining activity on the estate, and in this regard, assisted by his equally well-connected brother, John Lindsay, Lord Menmuir, (1552-1598) he invited two prospectors from Nuremberg, Germany, Bernard Fechtenburg and Hans Zeigler over to Scotland to prospect on his land.

Lord Edzell also played host to a number of distinguished guests, not least, Mary, Queen of Scots, who stayed at the estate for a time in August, 1562.

The Queen was roving Scotland at this time in an apparent attempt to quell the rebellious Earl of Huntly.

Whilst at Edzell, Mary convened a meeting of the Privy Council which was attended by the nobility of Scotland. Mary’s son, James VI visited Edzell twice, on 28 June, 1580, and in August, 1589.

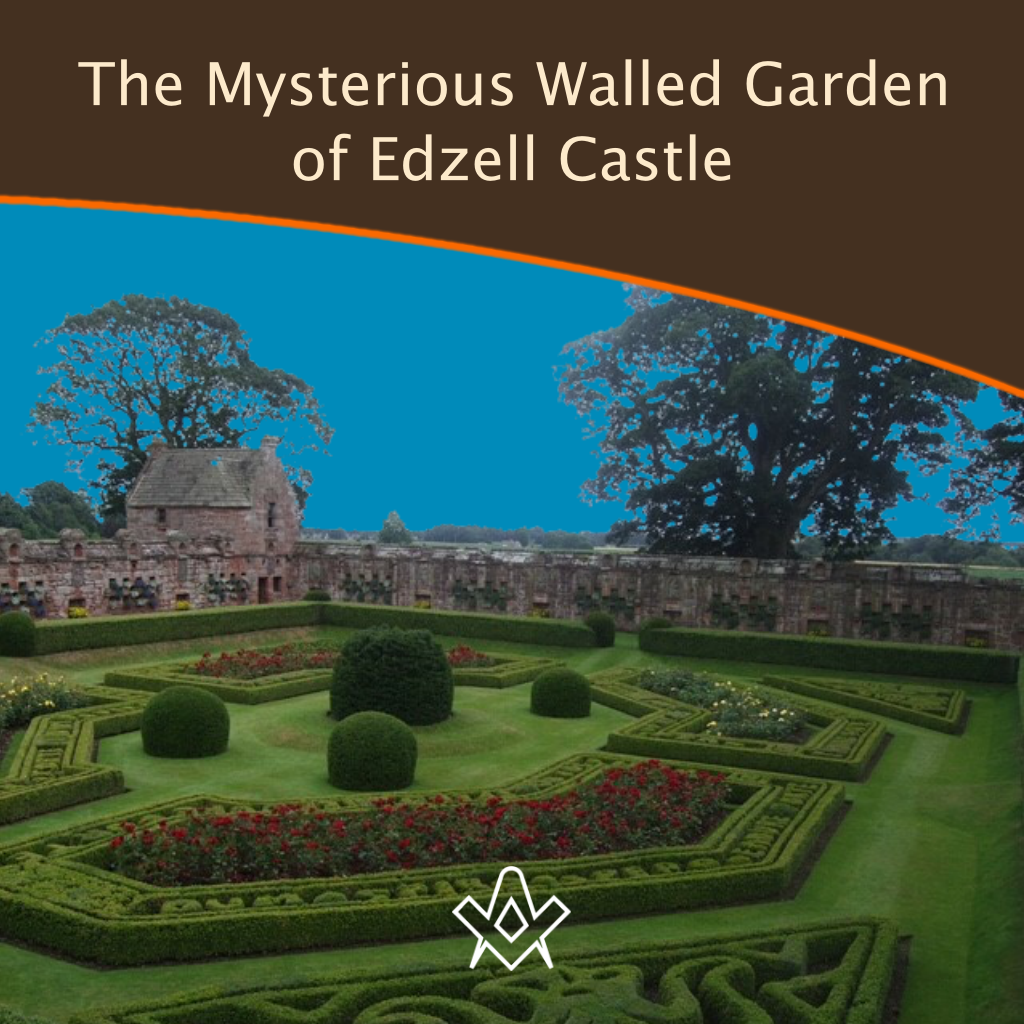

The Walled Garden

The Walled Garden

Photo: Copyright Author

Lord Edzell appears to have been a gentleman with an interest in all things esoteric and one of the many improvements he made to his property was the creation of a walled garden.

He added a large north range with rounded corner towers, and in 1604 he started the creation of the walled garden- or ‘Pleasaunce’, with the assistance of the aforementioned Fechtenburg and Zeigler, and which contained a number of remarkable features.

It seems there may have been a number of similar gardens in Scotland at that time, but the garden at Edzell, although much changed since 1604, is a rare example and few if any remain.

At this period in Scottish history, many people, particularly amongst the aristocracy were taking a keen interest in the subject of Hermeticism.

The Dominican Friar and Hermetic Philosopher, Giordano Bruno from Nola in Italy was living in London around this time and writing his treatises on the ‘Art of Memory’ as was his Scottish disciple Alexander Dicsone, who was born in the village of Errol in Perthshire, only a short distance from Edzell.

King James VI of Scotland took a keen interest in the subject, as did a number of members of his Royal Court, including the aforesaid Dicsone, Sir William Fowler, and the Kings Master of Works, one William Schaw, the so-called ‘Father of Scottish Freemasonry’, whose famous Schaw Statutes organised and formalised the operative Lodges of Stonemasons during that period.

It is believed that Lindsay created his garden in order to entertain distinguished visitors who may have shared his enthusiasm for such subjects.

The garden itself is a rectangular enclosure around 52 metres (170ft) from north to south, and 43.5 metres (143ft) from east to west, and enclosed with a wall 3.6 metres (12ft) high.

The north wall is effectively part of the castle’s courtyard wall, but the remaining three are deliberately and intricately designed with ornate carved panels.

The walls are separated into regular sections, once divided by pilasters which have now been removed.

The walls have been described thus:

Each compartment has a niche above, possibly once containing statues.

Those on the east wall have semi-circular pediments carved with scrolls, and with the national symbols of thistle, fleur-de-lis, shamrock and rose, recalling the union of the crowns of England and Scotland, under James VI in 1603.

The pediments on the south wall are square, while there are no niches on the west wall, indicating that work may have prematurely come to a halt of Sir David’s death. Below the niches, the compartments are of alternating design.

Three sets of seven carved panels occupy every other compartment.

Between them the walls are decorated with a representation of the Lindsay coat of arms, with eleven recesses in the form of a fess chequy, or chequered band, surrounded by three seven-pointed stars, taken from the Stirling of Glenesk arms.

Several spaces within the walls, including inside the stars, may have been intended as nesting-holes for birds.

Lindsay Coat of Arms

Photo: Copyright Author

The carved panels on the walls consist of the seven Cardinal Virtues on the west wall namely: depictions of the three Christian virtues (faith, hope and charity) as well as the four moral virtues:

- Fides (Faith) – this panel is damaged.

- Spes (Hope)

- Caritas (Charity)

- Prudentia (Prudence)

- Temperantia Temperance)

- Fortitudo (Fortitude)

- Justitia (Justice)

On the south wall are the seven Liberal Arts & Sciences of the trivium and quadrivium, namely:

- Grammatica (Grammar)

- Rhetorica (Rhetoric)

- Dialectica (Logic)

- Arithmetica (Arithmetic)

- Musica (Music) – this panel is damaged.

- Geometria (Geometry)

- Astronomia (Astronomy)

Rhetorica (Rhetoric) | Arithmetica (Arithmetic) | Geometria (Geometry)

Photo: Copyright Author

The seven Planetary Deities are on the west wall, namely:

- Luna

- Mercury

- Venus

- Sol

- Mars

- Jupiter

- Saturn

Mercury / Hermes

Photo: Copyright Author

The panels are approximately 1 metre (3.3 ft) high, by 60 to 75 cm (2 to 2 1/2 ft) in width.

The depictions of the deities are in elliptical shaped frames; the liberal arts depictions are situated under arches; and the cardinal virtues are in plain rectangles.

The panels depicting the Liberal Arts have been said to be the weakest carvings, and it is considered that by the time these panels were carved, Lindsay may have been running short of money for the project.

The carvings of the deities appear to bear a strong comparison to similar ones of the same vintage found in Aberdeenshire, suggesting that they were made by the same stonemason.

The carved panels at Edzell garden are based on patterns which were circulating at the time, many of which originated in Nuremberg in Germany, and it has been speculated that the aforementioned Hans Zeigler may have brought them over from Germany and showed them to Lindsay during his time at Edzell.

The images of the deities are thought derived from 1528-1529 engravings by the German artist Georg Pencz (also known as Iorg Bentz) who was a student of Albrecht Durer.

The initials “I.B.” certainly appear on the carving of ‘Mars’. The arts and virtues carvings are based on engravings by Johannes Sadeler and Crispijin de Passe which were distributed widely in Scotland at that time.

The arts and virtues carvings were derived from paintings of the engravings probably owned by Lindsay, his family and friends.

A bath-house and summer-house were added to the features of the garden. The bath-house is ruined, but the summer-house is still in excellent condition and is situated at the north-east corner of the garden.

The two-storey summer-house consists of a groin-vaulted lower room, which contains a round table and seating carved out of stone.

One can almost imagine Sir David Lindsay and his distinguished guests sitting around the table à la King Arthur and his knights of old, discussing their interests and the matters of the day.

The summer-house contains a room which stores the original planetary deity panels which have been taken indoors to prevent further erosion and which have been replaced with replicas.

The summer-house also contains a wood carved wall panel with a series of eight images, the most striking of which is one of Jesus Christ on the cross.

Of course, since it is a garden, there are a number of beautiful floral displays, and decorative hedges.

A number of the hedges have been shaped into the Scottish thistle, English rose, and French fleur-de-lis.

In addition, a number of the plantings have been formed in such a way as to show the mottoes of the Lindsay family: Dum Spiro Spero (While I Breathe I Hope) and Endure Forte (Endure Firmly).

wooden carved panel depicting eight images, including Jesus on the cross

Photo: Copyright Author

Walking around this garden, any Freemason, indeed, anyone with even a vague interest in esoteric matters, will be familiar with the subjects on the carved wall panels: the seven Liberal Arts and Sciences, which play a key role in Masonic symbolism, particularly in the Fellow Craft degree; and the three Christian virtues of Faith, Hope, and Charity, which again, are very important tenets of Freemasonry; and it is clear that the creator of this garden had very similar interests.

Incidentally, the carving of Prudence on the west wall of the garden is identical to that used by William Schaw in the pageantry celebrating the homecoming of James VI with his new wife Queen Anne to Scotland in 1589.

Author Kenneth Jack seated beneath ‘Prudence’

Photo: Copyright Author

As indicated earlier, Sir David Lindsay appears to have been part of a coterie of men of his time who were interested in esoteric subject matter.

His nephew, David Lindsay, 1st Lord Balcarres, certainly shared this interest, and is grouped with like-minded individuals who appear associated with the Rosicrucian movement.

As well-known Masonic and esoteric authority Robert A. Gilbert states in his paper Rosicrucians, True or False:

With all this in mind, it may now be helpful to review past forms of Rosicrucianism to separate the wheat from the chaff, the true from the false…

We know of no certain Rosicrucian institutions of the 17th century, although many esotericists and proto-freemasons had, or claimed to have, Rosicrucian associations: Elias Ashmole, Robert Fludd, Thomas Vaughan and Sir David Lindsay (Lord Balcarres) in Britain…

Thomas Vaughan

Thomas Vaughan (1622 – 1665) was an alchemist, qabalist, and Rosicrucian apologist, born in Llanaintffraid in Wales. He is renowned for his translation of the Rosicrucian Manifestos: Fama Fraternitatis and Confessio Fraternitatis.

He wrote a number of important magical and alchemical texts under the assumed pen-name of Eugenius Philalethes.

He was killed when one of his alchemical experiments went horribly wrong.

frontispiece of Fama Fraternitatis, 1614. By Johann Valentin Andreae – Norman MacKenzie, Secret Societies, London 1967

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Giving a flavour of so-called Rosicrucianism in Britain at that time, historian Christopher McIntosh in his book The Rosicrucians writes:

The Rosicrucian idea can be seen in England in two different streams which often converge.

On the one hand, the utopian stream represented by Comenius was concerned with social, scientific, and philosophical ideals.

On the other hand, the Hermetic-Quabalistic-alchemical stream was more concerned with the occult aspects of Rosicrucianism.

One representative of the second stream is Thomas Vaughan (1622 – 1656) who was the twin brother of the religious poet, Henry Vaughan. Vaughan can be considered the successor to Robert Fludd as the main English Rosicrucian apologist.

McIntosh goes on to describe how in 1650 Thomas Vaughan, using the pseudonym Eugenius Philalethes published his Anthroposophia Theomagica which he dedicated to the “Regenerated brethren R.C.”

McIntosh observes that this work appears to be the first apologia for the Rosicrucians written in the English language as opposed to the previous Latin.

Vaughan also published a number of English translation Rosicrucian tracts which included a preface under the same Philalethes pseudonym in 1652.

In the latter year, his English translation of The Fame and Confession of the Fraternity of R.C., Commonly, of the Rosie Cross, With a Præface annexed thereto, and a short declaration of their Physcicall Work, was first printed.

This printing was apparently taken from a manuscript copy that Vaughan had, ‘communicated to me by a gentleman more learned then myself, and I should name him here, but that he expects not either thy thanks or mine’.

Most scholars are settled on the high probability that Vaughan’s learned patron, Sir Robert Moray, one of the founders of the Royal Society, was his literary benefactor.

We will discuss where Sir Robert Moray sourced this manuscript shortly.

McIntosh continues:

Vaughan evidently based his translation of the Fama on a manuscript version in the possession of the Scottish Hermetist Sir David Lindsay, Earl of Bacarres (1585-1641) whose home Edzell Castle in Angus, had a remarkable ‘Garden of the Planets’, a walled enclosure with carved panels representing the seven planetary deities, the seven liberal arts, and the seven cardinal virtues.

An article by Adam McLean appeared in ‘The Hermetic Journal’, Mclean writes of Sir David Lindsay ‘He had connections with the Rosicrucians during the early part of the 17th century, and there are still preserved manuscript copies in his own hand of his alchemical notebooks, which include a translation of the Fama Fraternitatis, the first Rosicrucian Manifesto.

It is interesting that it has now been established that the first printed translation into English of the Fama, in 1652, although ascribed to Thomas Vaughan, is an adaptation of this earlier manuscript translation.

Vaughan must have had access to Sir David Lindsay’s MS and drew heavily upon it for his translation.

Perhaps Sir David’s MS was circulated around the alchemical / Rosicrucian adepts during the early decades of the seventeenth century, or could it rather be that people like Vaughan actually visited Edzell during that time?

McIntosh may be confused concerning the identities and titles of the various David Lindsays, which is not too surprising, given their shared names and interests.

The creator of the mysterious walled garden was in fact Sir David Lindsay, Lord Edzell, who was born in 1551 and who died on 14 December, 1610.

As stated earlier, this David did not inherit the title of Earl of Crawford from his father, but was knighted and took the Edzell title.

His nephew was David Lindsay, 1st Lord Balcarres who was born in 1587 and who died on 31 January, 1642.

The latter shared his uncle’s interest in Alchemy and Rosicrucianism, and it was he and his father Lord Menmuir, who built up the large library at Balcarres from which Vaughan may have obtained the Rosicrucian manuscripts.

The 1st Lord Balcarres undoubtedly would have been a fairly regular visitor to Edzell, along with others of similar persuasion.

The interesting fact about Sir David Lindsay, Lord Balcarres, is that his daughter Lady Sophia Lindsay was married to aforesaid Sir Robert Moray, also a famous figure in Masonic circles, and the patron of Thomas Vaughan.

This all plays quite neatly into the strong possibility that the source document Lord Lindsay used in his translation of the Fama, which he transcribed in his own hand in 1633, and which Vaughan is believed to have used for his first English translation, may well have come from Germany; by way of the German miners at Edzell, and the Lord’s father and uncle.

McIntosh further quotes McLean’s opinion of the walled garden at Edzell:

Of the garden, McLean writes: We can find something woven into its symbolic carvings reflecting the atmosphere which permeates the Rosicrucian document.

The Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosencreutz, an allegory of initiation, an important part of which is the leading of the hero or candidate before various sculptures and other ritual items which he has had to contemplate to absorb their significance…

So it is my thesis that the Edzell Garden of the Planets should be seen as an early seventeenth-century Mystery Temple connected with the Hermetic revival.

A carved plaque over the entrance bears the date 1604 (most likely the year of its foundation) and when one remembers that James VI, who had a great interest in and was patron of aspects of occultism, became King of the United Kingdom of Scotland and England in 1603, one realises that the building of this Mystery Temple was not taking place in a vacuum, but was part of a general renaissance of interest in Hermeticism in the society of that period.

Edzell was possibly a place of instruction in hermetic and alchemical philosophy and may have been a centre of Rosicrucian activity.

It would appear that Scotland played an important and possibly key role in the early development of Rosicrucianism.

This is an area of study which would clearly reward further research.

McLean, an acknowledged expert on the subject of Alchemy sees in the walled garden at Edzell, a similarity to Eliphas Levi’s description of the ancient Tarot of the Egyptians which they carved into the walls of their temples, where initiates were invited to visit and meditate upon, in what was obviously a contemplative and educational exercise.

Early Tarot packs apparently contained the Liberal Arts, Cardinal Virtues, and Seven Planets.

Mclean concludes of the walled-garden:

Little historical documentation has been preserved to indicate its use, but the stones remain, an eloquent reminder of the strength and inspiration of the Hermetic tradition in Scotland.

Rosicrucianism In Scotland

Rosicrucianism In Scotland

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Mclean is most certainly correct when he asserts that the building of the mysterious garden was not taking place ‘in a vacuum’.

Indeed, Lindsay started to create his garden in October, 1604, and in that same month a new star was discovered in the night sky, a Supernova, which many believed was a portent of a fresh period of spiritual growth and of great and momentous things to come.

The sighting of this star was allied to similar sightings at the time of the birth of Charlemagne and Jesus Christ himself (The Star of David).

Although the star was discovered by others, it was observed very closely by Johannes Kepler, a famous 17th century astronomer/astrologist, who is widely regarded as being a Rosicrucian, although critical of them at times.

He certainly moved in similar circles and attended the University at Tubingen in Germany, where Johann Valentin Andreae, the reputed author of the so-called Rosicrucian Manifestos also studied.

These manifestos started to appear in manuscript form throughout Europe from at least 1604 onwards. 1604 is the year in which the manifestos refer to the re-discovery and opening of the tomb of the mythical Rosicrucian hero, Christian Rosenkreutz.

The phenomenon of ‘new stars’ is referred to in one of the manifestos – the Confessio Fraternitatis:

Yea, the Lord God hath already sent before certain messengers, which should testify his will, to wit, some new stars, which do appear, and are seen in the firmament of Serpentaria and Cygno, which signify and give themselves known to everyone, that they are powerful Signacula of great weighty matters.

On the subject of the ‘new stars’ Christopher McIntosh writes:

That year (1604) saw the appearance of two new stars in the constellations of Serpentarius and Cygnos.

At the time when the new stars appeared, Jupiter and Saturn were in conjunction in the 9th house.

As Jupiter was considered a good planet and Saturn a bad one, there was some speculation as to which was dominant.

The general consensus, however, was that, as the 9th house is Jupiter’s house, and Jupiter rules Pisces, the sign which was in the ascendant at the time of the observation, Jupiter, was the dominant planet.

Both planets were also favourably placed, in relation to the other planets.

When Saturn is well placed, it brings forth thoughtful serious men.

It was believed that these astrological positions corresponded with those that were present at the date of creation itself.

The year 1604 then, was clearly seen as an optimum time for wise and righteous men, prophets if you will, to come forward and change society for the better and perhaps overthrow the excesses and prejudices of the ruling orthodoxy (the Roman Catholic Church).

Indeed, the Rosicrucian brotherhood had set out their stall.

McIntosh continues:

Thus, the signs at the appearance of the new stars in 1604 were the same as those for the beginning of the world, proving that 1604 would also see a great new beginning.

In the Rosicrucian context, this new beginning meant the opening of Christian Rosenkreutz’s tomb and the issuing forth of his message.

It is entirely possible then, that Scotland was not only the birthplace of speculative Freemasonry, but also the centre for the revival of Rosicrucianism in 17th century Britain, and that Edzell and its mysterious walled garden played host to a number of key players in the burgeoning Rosicrucian movement of the period.

It is very possible indeed, that the German miners who were brought over to Edzell Castle, brought with them Rosicrucian manuscripts from Germany, which were examined, discussed, and distributed to interested parties within the grounds of the mysterious walled garden.

The Lindsay family clearly had a deep and abiding interest in various aspects of the occult and Sir David Lindsay, Lord Balcarres, being a particularly studious individual, added considerably to the family library that his father had instigated, to such an extent that it was said: ‘He added to his father’s library till it became one of the best then to be met in Scotland’.

His daughter-in-law said of him: ‘He thought a day misspent on which he knew not a thing new’.

The latter statement immediately calls to mind the admonition given to all Freemasons to make a ‘daily advancement’ in their knowledge.

Balcarres was one of the subjects of a paper entitled: ‘Sketches of Later Scottish Alchemists’, published in the 1876 Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland:

Natural Philosophy, particularly chemistry, and the then fashionable quest of the elixir vitae (Elixir of Life), and the Philosopher’s Stone, occupied much of his attention; but it was the spirit of science and philanthropy, not of lucre, that animated his researches…..

Ten volumes of transcripts and translations from the works of the Rosicrucians and others, models of correct calligraphy, ‘which I remember seeing’, says one of his descendants’, ‘in our library covered over with the venerable dust (not gold dust) of antiquity, survived their author, but have now dwindled to four, which still hold their place in the Library of his representative along with his father’s well-read, Plato – the favourite author.

I have little doubt, of the son likewise’. This love for mysticism and occult science may probably have been imbibed during his early travels on the continent.

‘It is not impossible indeed that he may have become’ says Lord Lindsay, ‘a brother of the ‘Rosy Cross’, if indeed that celebrated society ever existed – it’s labours having been professedly devoted to the glory of God, and the good of mankind’.

This amiable nobleman died in 1641.

James Ludovic Lindsay

Evidently, the Lindsay family were genetically predisposed to Freemasonry and like esoteric movements, as we know later descendants were also fascinated with the subjects.

James Ludovic Lindsay, was noted for his interest in Freemasonry and the occult.

He was born on 28 July, 1847 in Saint-Germaine-en-Laye, Ile-De-France, France, the son of Alexander William Crawford Lindsay, 25th Earl of Crawford, and he eventually succeeded his father becoming 26th Earl of Crawford and 9th Earl of Balcarres.

Statesmen No. 263: Caricature of James, Lord Lindsay MP (1847-1913), later 26th Earl of Crawford. Caption read ‘Astronomy, Vanity Fair, May 1878

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

James became a noted astronomer and philatelist and divided his time between the family estates in Wigan, England, and Balcarres in Scotland.

He was a member of Masonic Lodges in both Wigan and Edinburgh and a notable figure within the Craft in England and Scotland.

Along with his father he assembled a large collection of literature known as Bibliotheca Lindesiana which became renowned for its size, and the rarity of some of the books held.

The main part of the collection was retained at Haigh Hall in Wigan, but some were held at the family home at Balcarres, and must surely have included many of the esoteric materials previously owned by their distinguished ancestors. James also found time to be a Conservative Member of Parliament and a member of the Royal Society.

In a bizarre incident from his eventful life, James Lindsay, who was a follower of the spiritualist Daniel Douglas Home, apparently witnessed Home levitate out of the window of a third-floor room, and return via an adjoining room.

Lindsay’s interest in this subject was shared by contemporaries and fellow Freemasons such as the famous author, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and architect and archaeologist, Frederick Bligh Bond.

Lindsay was clearly a keen student of the occult and spiritualism, and is said to have been possessed of psychic ability himself.

With regards to the library at Haigh Hall, Wigan, it is an interesting sidelight that in 1903, noted Rosicrucian scholar, the Reverend James Brown Craven, of Kirkwall, Orkney, in the course of his research into Rosicrucianism, requisitioned a number of items of literature from the librarian at Haigh Hall, Mr. J. P. Edmond, which undoubtedly was of great assistance to his valuable accounts of the works of Rosicrucian apologists: Michael Maier, Robert Fludd, and Heinrich Khunrath.

Whatever Sir David Lindsay, Lord Edzell’s motivations were for creating the mysterious walled garden at Edzell in 1604, there is no doubt that it is a curious and beautiful enigma of a place, and a stroll around it, and the nearby castle ruin, is a most peaceful and serene experience.

The castle and gardens are maintained by Historic Scotland, and in normal times are open to the public all year round.

They are a must-see for all true seekers interested in Scotland’s Rosicrucian heritage.

Further study:

Adam McLean’s comprehensive website on all things alchemical https://www.alchemywebsite.com/index.html

Article by: Kenneth C. Jack

Kenneth C. Jack FPS is an enthusiastic Masonic researcher/writer from Highland Perthshire in Scotland.

He is Past Master of a Craft Lodge, Past First Principal of a Royal Arch Chapter, Past Most-Wise Sovereign of a Sovereign Chapter of Princes Rose Croix.

He has been extensively published in various Masonic periodicals throughout the world including: The Ashlar, The Square, The Scottish Rite Journal, Masonic Magazine, Philalethes Journal, and the annual transactions of various Masonic bodies.

Kenneth is a Fellow of the Philalethes Society, a highly prestigious Masonic research body based in the USA.

The Magical Calendar

By: Adam McLean

The Magical Calendar is one of the most amazing and comprehensive tables of Celestial and magical correspondences ever published, and is one of the most important documents from the seventeenth-century renaissance of magical symbolism that focused around the Rosicrucian movement.

Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition

By: Frances A. Yates

Placing Bruno—both advanced philosopher and magician burned at the stake—in the Hermetic tradition, Yates’s acclaimed study gives an overview not only of Renaissance humanism but of its interplay—and conflict—with magic and occult practices.

The Rosicrucian Fama Fraternitatis and Confessio Fraternitatis

By: Christian Rosenkreuz

Dating to 1614 and 1615, these are two of the three primary documents which originally announced and helped define who the secret society of Rosicrucians were. These works, written in veiled and alchemical language, outline the true philosophy of RC along with a code of conduct that members are expected to live by. These two pieces have been the subject of serious occult study for centuries since their first appearance.

Recent Articles: Kenneth C. Jack

Observations on the History of Masonic Research Archaeology is often associated with uncovering ancient tombs and fossilized remains, but it goes beyond that. In a Masonic context, archaeology can be used to study and analyze the material culture of Freemasonry, providing insight into its history and development. This article will explore the emergence and evolution of Masonic research, shedding light on the challenges faced by this ancient society in the modern world. |

Anthony O'Neal Haye – Freemason, Poet, Author and Magus Discover the untold story of Anthony O’Neal Haye, a revered Scottish Freemason and Poet Laureate of Lodge Canongate Kilwinning No. 2 in Edinburgh. Beyond his Masonic achievements, Haye was a prolific author, delving deep into the history of the Knights Templar and leaving an indelible mark on Scottish Freemasonry. Dive into the life of a man who, despite his humble beginnings, rose to prominence in both Masonic and literary circles, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire. |

Rosicrucianism and the Gowrie House Mystery Unearth the mystifying intersections of Rosicrucianism and the infamous Gowrie House Mystery. Dive into speculative claims of sacred knowledge, royal theft, and a Masonic conspiracy, harking back to a fateful day in 1600. As we delve into this enthralling enigma, we challenge everything you thought you knew about this historical thriller. A paper by Kenneth Jack |

Thomas Telford's Masonic Bridge of Dunkeld Of course, there is no such thing as a ‘Masonic Bridge’; but if any bridge is deserving of such an epithet, then the Bridge of Dunkeld is surely it. Designed by Scotsman Thomas Telford, one of the most famous Freemasons in history. |

The masonic and orange orders: fraternal twins or public misperception? “Who’s the Mason in the black?” |

Kenneth Jack's research reveals James Murray, 2nd Duke of Atholl – the 'lost Grand Master' |

An Oration delivered to the Annual Burns and Hogg Festival, at Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No. 2, Edinburgh, on 24 January 2018. By Bro. Kenneth C. Jack, FSAScot FPS, Past Master, Lodge St. Andrew, No. 814, Pitlochry. |

William Winwood Reade was a Scottish philosopher, historian, anthropologist, and explorer born in Crieff, Perthshire, Scotland. The following article by Kenneth Jack, provides some hints that William may have been a Freemason, but there is presently no definitive evidence he was. |

What's in a name? A brief history of the first Scottish Lodge in Australia - By Brother Kenneth C. Jack, Past Master, Lodge St. Andrew, No. 814, Pitlochry |

Sir Francis Bacon and Salomon’s House Does Sir Francis Bacon's book "The New Atlantis" indicate that he was a Rosicrucian, and most likely a Freemason too? Article by Kenneth Jack |

George Blackie – The History of the Knights Templar P.4 The final part in the serialisation of George Blackie's 'History of the Knights Templar and the Sublime Teachings of the Order' transcribed by Kenneth Jack. |

George Blackie – The History of the Knights Templar P.3 Third part in the serialisation of George Blackie's 'History of the Knights Templar and the Sublime Teachings of the Order' transcribed by Kenneth Jack. |

George Blackie – The History of the Knights Templar P.2 Second part in the serialisation of George Blackie's 'History of the Knights Templar and the Sublime Teachings of the Order' transcribed by Kenneth Jack. |

George Blackie – The History of the Knights Templar P.1 First part in the serialisation of George Blackie's History of the Knights Templar and the Sublime Teachings of the Order – by Kenneth Jack |

Little known as a Freemason, Bro Dr Robert ‘The Bulldog’ Irvine remains a Scottish rugby legend, and his feat of appearing in 10 consecutive international matches against England has only been surpassed once in 140 years by Sandy Carmichael. |

Rev. J.B. Craven: Theologian, Historian, Freemason, And Rosicrucian Scholar Archdeacon James Brown Craven is one of those unsung heroes of Scottish Freemasonry about whom very little has been previously written – here Kenneth Jack explores the life and works of this remarkable esoteric Christian. |

Discover the powerful family of William Schaw, known as the 'Father of Freemasonry' |

This month, Kenneth Jack invites us to look at the life of Sir William Peck; - astronomer, Freemason and inventor of the world's first electric car. A truly fascinating life story. |

A Tribute to Scotland's Bard – The William Robertson Smith Collection With Burns' Night approaching, we pay tribute to Scotland's most famous Bard – The William Robertson Smith Collection |

The Joy of Masonic Book Collecting Book purchasing and collecting is a great joy in its own right, but when a little extra something reveals itself on purchase; particularly with regards to older, rarer titles.. |

Masons, Magus', and Monks of St Giles - who were the Birrell family of Scottish Freemasonry? |

The 6th Duke of Atholl - Chieftain, Grand Master, and a Memorial to Remember In 1865, why did over 500 Scottish Freemasons climb a hill in Perthshire carrying working tools, corn, oil and wine? Author Kenneth Jack retraces their steps, and reveals all. |

Charles Mackay: Freemason, Journalist, Writer Kenneth Jack looks at life of Bro Charles Mackay: Freemason, Journalist, Writer, Poet; and Author of ‘Tubal Cain’. |

A Mother Lodge and a Connection Uncovered, a claim that Sir Robert Moray was the first speculative Freemason to be initiated on English soil. |

What is it that connects a very old, well-known Crieff family, with a former President of the United States of America? |

The life of Bro. Cattanach, a theosophist occultist and Scottish Freemason |

The Mysterious Walled Garden of Edzell Castle Explore the mysterious walled garden steeped in Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, and Hermeticism. |

Dr. George Dickson: Scottish Freemason and Occultist Bro. Kenneth explores the life of Dr George Dickson a Scottish Freemason and Occultist |

The Colour Purple - Its Derivation and Masonic Significance What is the colour purple with regards to Freemasonry? The colour is certainly significant within the Royal Arch series of degrees being emblematical of Union. |

Bridging the Mainstream and the Fringe Edward MacBean bridging mainstream Freemasonry with the fringe esoteric branches of Freemasonry |

Freemasonry in the Works of John Steinbeck We examine Freemasonry in the Works of John Steinbeck |

Renegade Scottish Freemason - John Crombie Who was John Crombie and why was he a 'renegade'? |

Scottish Witchcraft And The Third Degree How is Witchcraft connected to the Scottish Third Degree |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device