The issue of Bro. Ward’s series of handbooks cannot fail to accomplish its main object, which is to lead not only juniors, but also those well versed in the ritual, to mark, learn and inwardly digest the significance of the ceremonies, which when properly understood, causes our jewels and emblems to glow with an inner light which infinitely enhances their beauty.

– the Hon. Sir John A. Cockburn

Introduction Excerpt

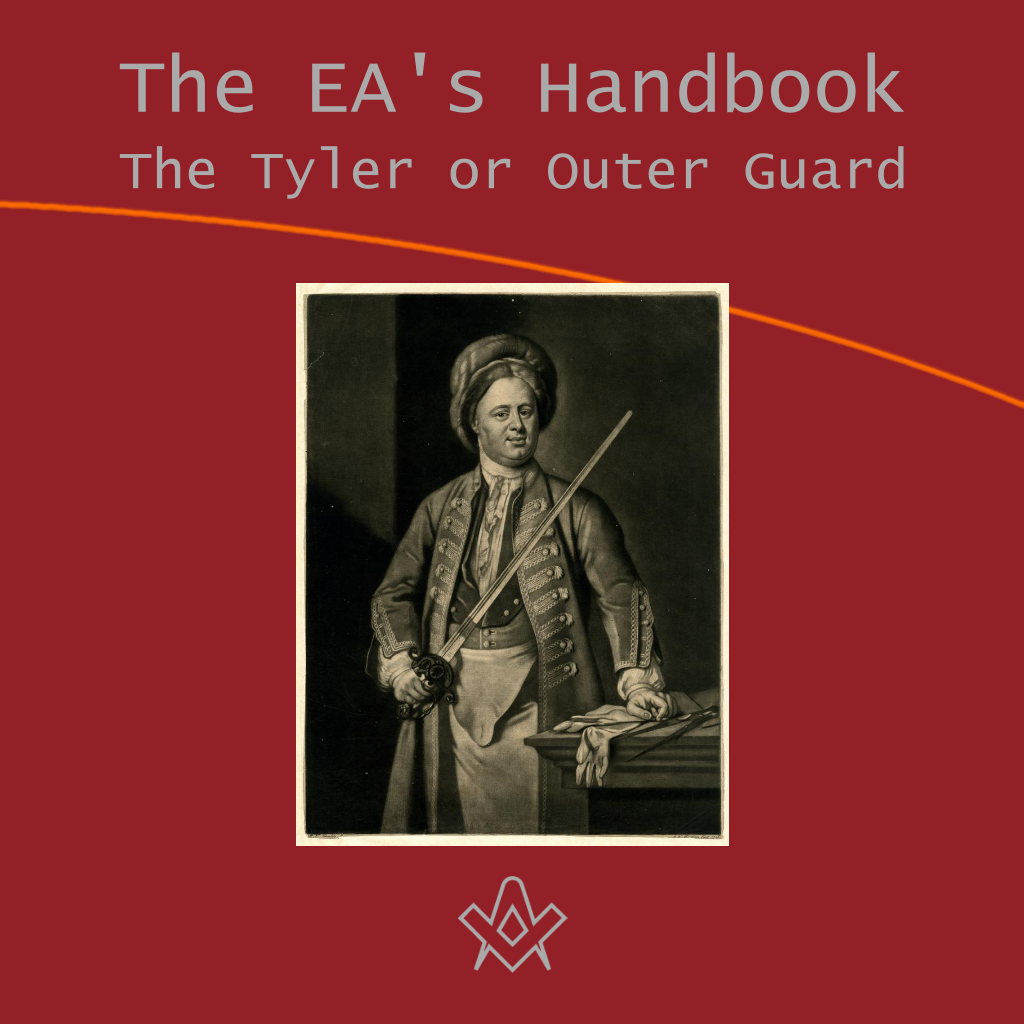

CHAPTER II – The Tyler

The first thing that greets the eyes of the aspirant to our Order is a man, whom he soon discovers is called the Tyler, standing in front of the door with a drawn sword in his hand.

He naturally wants an answer to the question which actually occurs in a certain famous old ritual, “Why does the Tyler wear a sword ?”-and the answer is, “To guard the brethren and to hele the Word.”

Let us consider this answer:- “To guard the brethren. “In certain old rituals of the 18th century we are told that Masons’ Lodges formerly met in the open- “on the highest hill or lowest valley, where never dog barked nor cock crew.”

Brethren will no doubt have read the interesting article in the “Masonic Record” relating to this state of affairs, but I am bound to say that I do not think that the ordinary mediaeval lodge met in such places.

The reference to the cock, together with certain details we possess with regard to those lodges which did meet in the open, (they were mostly in Scotland) indicate that they were not ordinary Craft lodges, but much more probably Templar Lodges.

The Templars

The Templars in the 18th century claimed to be descended from a body which had been suppressed in the years 1307 to 1314-, and actually prescribed.

There was every reason therefore why they should meet in out of the way places, but no such reason existed in the case of a lodge of ordinary Freemasons.

That such a phrase should have wandered into a craft ritual from Templary is perfectly natural, but it is not safe to argue from this that all Masonic lodges met under the canopy of heaven.

In those early days, many higher degrees were worked in ordinary Craft Lodges, in a way not permitted to-day; and this may easily account for phrases more appropriate to a Templar Preceptory being found in a Craft working.

I might add that until the middle of the 19th century Templar meetings were always called “Encampments,” indicating that they were camps held in the open fields.

But in mediaeval times we know that the Freemasons had Lodge buildings, and if they went to a new place to build a church or castle , the first thing they did was to erect a temporary Lodge room, which they attended before starting the day’s work.

Those interested will find abundant details in Fort Newton’s interesting little book, “The Builders.”

There also it is clearly shown that there were two kinds of masons in those days, and the man who conclusively proved this was not a modern Speculative Freemason.

The two groups were the Freemasons and the Guild Masons. The former were lineal descendants of the Comacine Masons-who, incidentally, knew a certain Masonic Sign-and these men were skilled architects, free to go anywhere.

They had a monopoly of ecclesiastical building and of work outside the towns, e.g. castles. The Guild Masons were humbler folk.

They were not allowed to build outside their particular city, but had a monopoly of all building inside that city, with one important and significant exception:-they were not allowed to build ecclesiastical buildings.

In return for their charter they had to maintain the fortifications. When a church had to be built the Freemasons were sent for, and apparently they called on the Guild Masons to help them with the rough work, e.g., to square the stones, etc.

I suggest that Speculative Freemasonry is mainly descended from the Freemasons, whereas the few Operative Lodges that survive are probably descended from the Guild masons.

This theory is borne out by the fact that while the Operatives have our grips they have not our signs, yet these signs are unquestionably old.

They would all have the same grip for convenience in proving to the Freemasons that they were really masons, but they would keep their signs to themselves, as did the Freemasons, since they did not want the other group to have access to their private meetings.

Further, we find that the Master Masons of the Freemasons were entitled to maintenance as “gentlemen,” clearly indicating that they were different from ordinary craftsmen (See Fort Newton).

After the Reformation no doubt Freemasons and Guild masons tended to amalgamate, and this explains much.

Now if the Freemasons erected a lodge before they started to build a church or castle, we shall see that their meeting in the open would be merely occasional, e.g., while the temporary lodge was being built, and not a regular custom ; but the very fact that is was a temporary building, and open to approach by all and sundry who came to the site of the new edifice, is quite sufficient to explain why they had someone on guard.

Why, however, is he called a Tyler, instead of Sentinel, or some similar name? There are three explanations, and we can adopt which we please:-

1. To tile is to cover in; hence the Tyler is one who covers or conceals what is going on in the lodge.

2. In the old mediaeval Templar ceremony there were three sentinels; one inside the door, one outside, and one on the roof or tiles, who could see if anyone was approaching the building. It will be remembered that the old Templar Churches were round, so that a man perched on the roof was able to see in every direction.

3. That the tilers were inferior craftsmen as compared with the genuine Freemasons; poor brethren, as it were, and not admitted to full membership, although one or two were chosen to act as Outer Guards.

Dry Wall Stone

I am not greatly impressed with the latter theory, and my person predilection is in favour of No. 1 ; but there is a good deal to be said for No. 2.

The Tyler guarded the brethren from “cowans” or eavesdroppers.

The former word is still used in the country districts of Lancashire and Westmorland for a dry-dyker, that is, a man who builds rough walls between the different fields, of rough, uncut, and un-mortared stones.

When I was living in Yorkshire I had a number of fields so surrounded; the stones for which were picked from the hillside, and piled one upon another.

No particular skill was needed to build such a wall; I repaired several myself.

In other words, a “cowan” is one who pretends to be a mason because he works in stone, but is not one. Some fanciful derivations have been suggested from “Cohen,” the Jewish priest. I disagree entirely with this view.

Why should the Jewish Cohens be more likely to pretend to be Freemasons than any other priests?

As the other word is spelt as we spell ours, and means what I have stated, I see no reason to invent this suggestion regarding the Jewish priests, who were always few in number, and in the Middle Ages hardly existed:- the Jews were driven out of England by Edward I., and not re-admitted until the time of Cromwell. “Eavesdroppers” means men who listen under the eaves.

Mediaeval Eaves

The eaves of a primitive or of a mediaeval cottage overhung a considerable distance beyond the walls, and between the roof and the wall was an open space.

Through this space the smoke of the fire escaped; the general arrangement being very similar to that found in the tropics.

The walls of such a cottage were often only five to six feet high, and thus a man could stand under the eaves in the shadow, hidden from the light of the sun or moon, and both see and hear what was going on inside, without those who were in the lodge knowing he was there.

But the Tyler was on guard outside the door of the Lodge; he was armed with a drawn sword, and woe betide any eavesdropper he discovered, for our mediaeval brethren undoubtedly interpreted their obligations literally.

Incidentally, I understand that nominally the duty of carrying out the penalty still rests on the shoulders of the Tyler.

With regard to the use of temporary buildings on or near the site of the edifice, it should be noted that during the building of Westminster Abbey there was at least one, if not two, such lodges, and they are mentioned in the records of the Abbey.

One seems to have stood on the site of the subsequent nave. Thus we can see that it was essential that there should be an Outer Guard to keep off intruders, owing to the fact that Lodges were usually held in temporary buildings, often with overhanging eaves and an open space between the top of the walls and the beams which supported the roof.

The word “hele” should, in my opinion, be pronounced “heal,” not “hale.”

The use of “hale” is due to the fact that in the 18th century the words “conceal,” and “reveal,” were pronounced “concale” and “revale.” Since the words obviously were a jingle, I consider it is more correct to-day to pronounce it “heal.”

Moreover, the word “hele” means to cover over.

You still hear the phrase used, “to hele a cottage,” or even a haystack, and the word “Hell” implies the place that is covered over, e.g., in the centre of the earth.

“Hele” is connected with “heal”-to cover up, or to close up, a wound-and the meaning therefore is tautological, viz, “to cover up the word.” (The Masonic secret)

The use of the pronunciation “Hale” is to-day most misleading, and is apt to cause a newly initiated Bro. to think he has to “hail” something, or “proclaim it aloud.”

The Candidate is taken in hand by the Tyler, who makes him sign a form to the effect that he is free and of the full age of 21 years.

Why “free?” Well, in mediaeval days he had to bind himself to serve as an apprentice for seven years.

Unless he was a free man, his owner might come along and take him away, before he had completed his apprenticeship and, worse still, might extort from him such secrets as he had learnt from the masons.

Thus the master might be enabled to set himself up as a free-lance, not under the control of the fraternity.

The twenty-one years is, I believe, an 18th century Speculative innovation, aiming at a similar object.

I think there is no doubt that usually in the Middle Ages an apprentice was a boy, who placed himself under the control of a Master with his parents’ consent.

The Master was henceforth in loco parentis. In the 18th century without some such safeguard (as 21 years) some precocious youth might have joined the fraternity without his father’s consent.

The father might have been one who disapproved of Freemasonry, and in such a case would probably have not hesitated to exercise his parental authority in the drastic manner at that time in vogue, and so exhort the secrets, which he could then have “exposed.”

To-day it is still a very reasonable clause, for it presupposes that man has reached years of discretion and knows what he is about.

Any real hardship is removed by the fact the Grand Lodge. has power to dispense, which power it constantly uses in the case of the University Lodges at Oxford and Cambridge.

I myself was one of those who thus benefited. It is, I believe, still the custom in England that a Lewis, the son of a mason, may be admitted at 18, though the right is seldom claimed; but in some countries, I understand, it is a privilege highly valued, and regularly used by those entitled to it.

Lewis: metal cramp to lift a stone

In masonry a Lewis is a cramp of metal, by which one stone is fastened to another.

It is usually some form of a cross, and a whole chapter could be written on its significance, but this casual reference must suffice.

[Age of admission varies by jurisdiction and Grand Lodge, UGLE has reduced the minimum age from 21 to 18]

Article by: J. S. M. Ward

John Sebastian Marlow Ward (22 December 1885 – 1949) was an English author who published widely on the subject of Freemasonry and esotericism.

He was born in what is now Belize. In 1908 he graduated from the University of Cambridge with honours in history, following in the footsteps of his father, Herbert Ward who had also studied in history before entering the priesthood in the Anglican Church, as his father had done before him.

John Ward became a prolific and sometimes controversial writer on a wide variety of topics. He made contributions to the history of Freemasonry and other secret societies.

He was also a psychic medium or spiritualist, a prominent churchman and is still seen by some as a mystic and modern-day prophet.

Recent Articles: J.S.M Ward EAF Handbook

Book Review - The EA, FC, MM Handbooks

Essential reading for every Entered Apprentice, Fellowcraft, and Master Mason - these seminal books by J.S.M Ward are what every Mason needs!

more....

The Entered Apprentices Handbook P1 Chapter 1 - An interpretation of the first degree, the meaning of the preparation, symbolism, ritual and signs. Chapter 1, The opening of the First Degree |

The Entered Apprentices Handbook P2 Chapter 2 - The Tyler or Outer Guard. The first thing that greets the eyes of the aspirant to our Order standing in front of the door with a drawn sword in his hand. |

The Entered Apprentices Handbook P3 Chapter 3 - the Candidate being prepared by the Tyler. What we now have is a system by which the parts which have to be bare are made bare. |

The Entered Apprentices Handbook P4 Chapter 4 - The candidate's admission into the lodge, is received on a sharp instrument. This signifies many things, one idea lying within the other. |

The Entered Apprentices Handbook P5 Chapter 5 - In all the ancient mysteries a candidate obligation was exacted to secure the secret teachings given in these mysteries which disclosed an inner meaning. |

The Entered Apprentices Handbook P6 Chapter 6 - Having taken the first regular step the Candidate is given the Sign. This he is told refers to the Penalty of his Obligation, and no doubt it does, but it also seems to refer to something much more startling. |

The Entered Apprentices Handbook P7 Chapter 7 - The candidate receives the charge, the first significant point is the phrase "Ancient, no doubt it is, as having subsisted from time immemorial". |

In the second volume we are dealing with the degree of Life, in its broadest sense, just as in the first degree we were dealing with the degree of birth, and as life in reality is educational for the Soul, we are not surprised to find that throughout the whole degree the subject of education is more or less stressed. read the full series … |

The third degree in Freemasonry is termed the Sublime Degree and the title is truly justified. Even in its exoteric aspect its simple, yet dramatic, power must leave a lasting impression on the mind of every Cand.. But its esoteric meaning contains some of the most profound spiritual instruction which it is possible to obtain to-day. read the full series … |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device