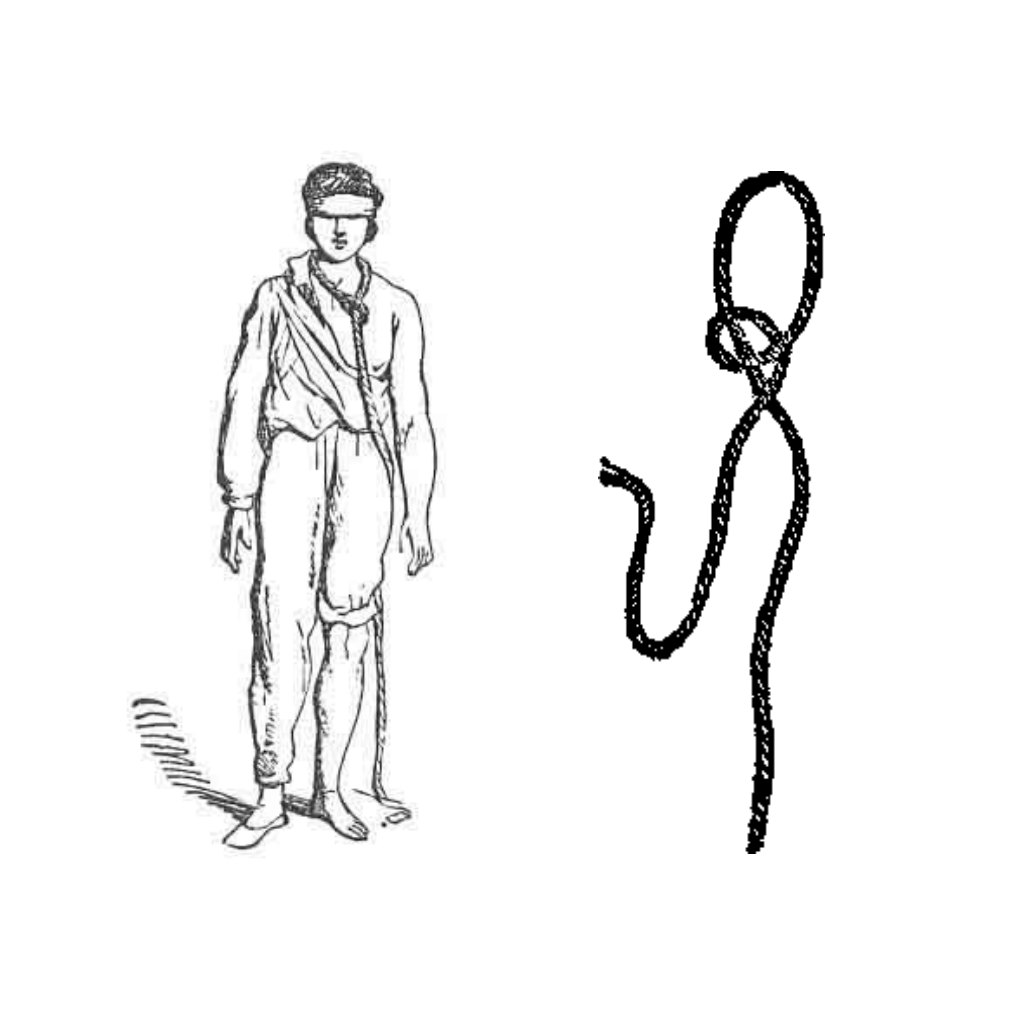

The ‘cable-tow’ or ‘noose’ is used in Craft Masonry as part of the ritual, as are ropes and ties in other degrees.

In old rituals it was called the ‘cable rope’ and our term is probably derived from the German kabeltauw. It is a very old symbol, and therefore was ever regarded as solely symbolic in nature.

However, in Craft Freemasonry, in the degree of Raising the reference is made; ‘If within the length of my cable-tow’.

This must assume that if a brother is not ‘within’, he is ‘excused’ attending lodge.

How can this be if the ‘length’ of a cable-tow is not a physical distance but merely an allegorical construct?

Masonic ritual is particularly quiet about ‘length’ (sic) with wording very elusive. Formerly, a cable-tow was deemed to be the distance one could travel in an hour, which was assumed to be about three miles.

Albeit some authorities, such as [Emanuel] Zimmerman noted various distances:

The cable tow of a(n) apprentice is fifite(en) Enches, that is from ye tip if ye tong to ye Senter of ye heart.

Later, after the Fellow Craft Obligation he wrote:

another rison for ye Cable tow of a Craft to be 15 1/2 miles because there was 15 P’ 2 Milles distance from ye temple to the place where ye stones where route (wrought).

The allegory is here amply illustrated by an unknown author in the 1920s:

The cable-tow, we are told, is purely Masonic in its meaning and use. It is so defined in the dictionary, but not always accurately, which shows that we ought not to depend upon the ordinary dictionary for the truth about Masonic terms.

Masonry has its own vocabulary and uses it in its own ways. Nor can our words always be defined for the benefit of the profane.

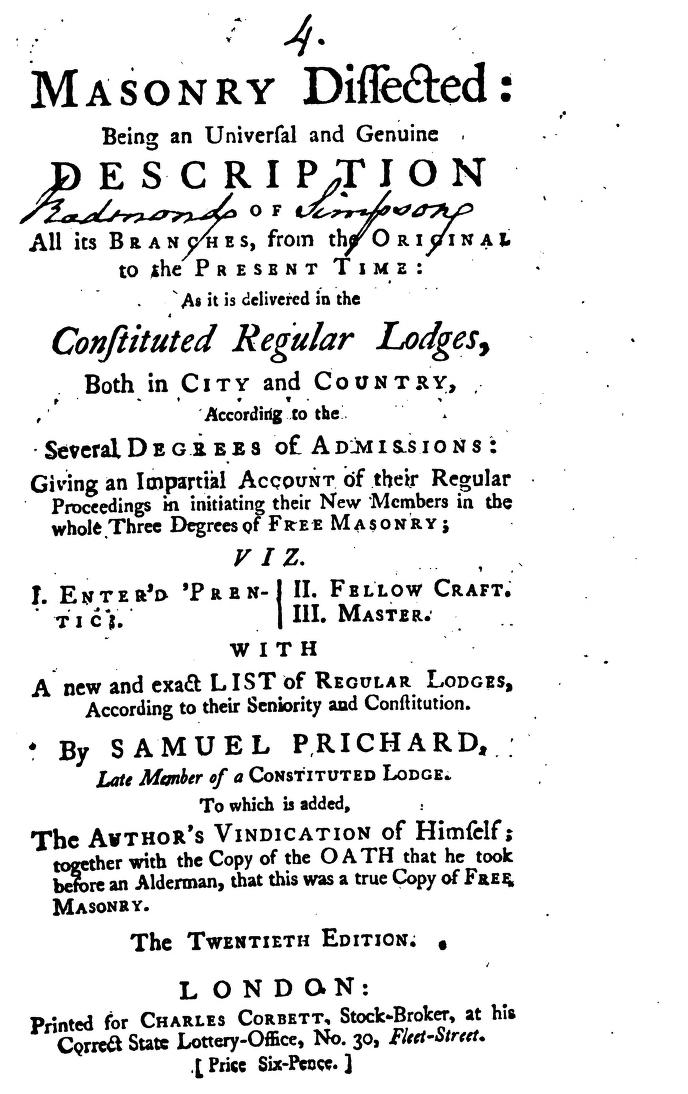

Even in Masonic lore the word cable-tow varies in form and use. In an early pamphlet by Pritchard, issued in 1730, and meant to be an exposure of Masonry, the cable-tow is called a ‘Cable-Rope’, and in another edition a ‘Tow-Line’.

The same word ‘Tow-Line’ is used in a pamphlet called ‘A Defense of Masonry,’ written, it is believed, by Anderson as a reply to Pritchard about the same time.

In neither pamphlet is the word used in exactly the form and sense in which it is used today; and in a note Pritchard, wishing to make everything Masonic absurd, explains it as meaning ‘The Roof of the Mouth!’

In English lodges, the cable-tow, like the hoodwink, is used only in the first degree, and has no symbolical meaning at all, apparently.

In American lodges it is used in all three degrees and has almost too many meanings.

Samuel Pritchard’s ‘Masonry Dissected

IMAGE LINKED: archive.org Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Some of our American teachers – Pike among them – see no meaning in the cable-tow beyond its obvious use in leading an initiate into the lodge, and the possible use of withdrawing him from it should he be unwilling or unworthy to advance.

To some of us this non-symbolical idea and use of the cable-tow is very strange, in view of what Masonry is in general, and particularly in its ceremonies of initiation.

For Masonry is a chamber of imagery. The whole Lodge is a symbol. Every object, every act is symbolic. The whole fits together into a system of symbolism by which Masonry veils, and yet reveals, the truth it seeks to teach to such as have eyes to see and are ready to receive it.

As far back as we can go in the history of initiation, we find the cable-two, or something like it, used very much as it is used in a Masonic Lodge today.

No matter what the origin and form of the word as we employ it may be – whether from the Hebrew ‘khabel’, or the Dutch ‘cabel’, both meaning a rope – the fact is the same.

In India, in Egypt and in most of the ancient Mysteries, a cord or cable was used in the same way and for the same purpose.

The meaning, so far as we can make it out, seems to have been some kind of pledge – a vow in which a man pledged his life.

Even outside initiatory rites we find it employed, as, for example, in a striking scene recorded in the Bible (I Kings 20:31, 32), the description of which is almost Masonic.

The King of Syria, Ben-hadad, had been defeated in battle by the King of Israel and his servants are making a plea for his life.

They approach the King of Israel ‘with ropes upon their heads,’ and speak of their ‘Brother, Ben-hadad’. Why did they wear ropes, or nooses, on their heads?

Slaughter of the Syrians by the Children of Israel – Gustave Dore Bible Gallery 1 Kings 20

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Evidently to symbolize a pledge of some sort, given in a Lodge or otherwise, between the two Kings, of which they wished to remind the King of Israel. The King of Israel asked: ‘Is he yet alive? He is my brother.’

Then we read that the servants of the Syrian King watched to see if the King of Israel made any sign, and, catching his sign, they brought the captive King of Syria before him. Not only was the life of the King of Syria spared, but a new pledge was made between the two men.

The cable-tow, then, is the outward and visible symbol of a vow in which a man has pledged his life or has pledged himself to save another life at the risk of his own.

Its length and strength are measured by the ability of the man to fulfil his obligation and his sense of the moral sanctity of his obligation – a test, that is, both of his capacity and of his character.

If a lodge is a symbol of the world, and initiation is our birth into the world of Masonry, the cable-tow is not unlike the cord which unites a child to its mother at birth; and so, it is usually interpreted.

Just as the physical cord, when cut, is replaced by a tie of love and obligation between mother and child, so, in one of the most impressive moments of initiation, the cable-tow is removed, because the brother, by his oath at the Altar of Obligation, is bound by a tie stronger than any physical cable.

What before was an outward physical restraint has become an inward moral constraint.

That is to say, force is replaced by love – outer authority by inner obligation – and that is the secret of security and the only basis of brotherhood.

The cable-tow is the sign of the pledge of the life of a man. As in his oath he agrees to forfeit his life if his vow is violated, so, positively, he pledges his life to the service of the Craft.

He agrees to go to the aid of a Brother, using all his power in his behalf, ‘if within the length of his cable-tow,’ which means, if within the reach of his power.

How strange that any one should fail to see symbolical meaning in the cable-tow. It is, indeed, the great symbol of the mystic tie which Masonry spins and weaves between men, making them Brothers and helpers one of another.

But, let us remember that a cable-tow has two ends. If it binds a Mason to the Fraternity, by the same fact it binds the Fraternity to each man in it.

The one obligation needs to be emphasized as much as the other. Happily, in our day we are beginning to see the other side of the obligation – that the Fraternity is under vows to its members to guide, instruct and train them for the effective service of the Craft and of humanity.

Control, obedience, direction or guidance – these are the three meanings of the cable-tow, as it is interpreted by the best insight of the Craft.

By Control we do not mean that Masonry commands us in the same sense that it uses force. Masonry rules men as beauty rules an artist, as love rules a lover. It does not drive; it draws.

It controls us, shapes us through its human touch and its moral nobility. By the same method, by the same power it wins obedience and gives guidance and direction to our lives.

At the Altar we take vows to follow and obey its high principles and ideals; and Masonic vows are not empty obligations – they are vows in which a man pledges his life and his sacred honour.

Source: Short Talk Bulletin – Mar. 1926

Masonic Service Association of North America

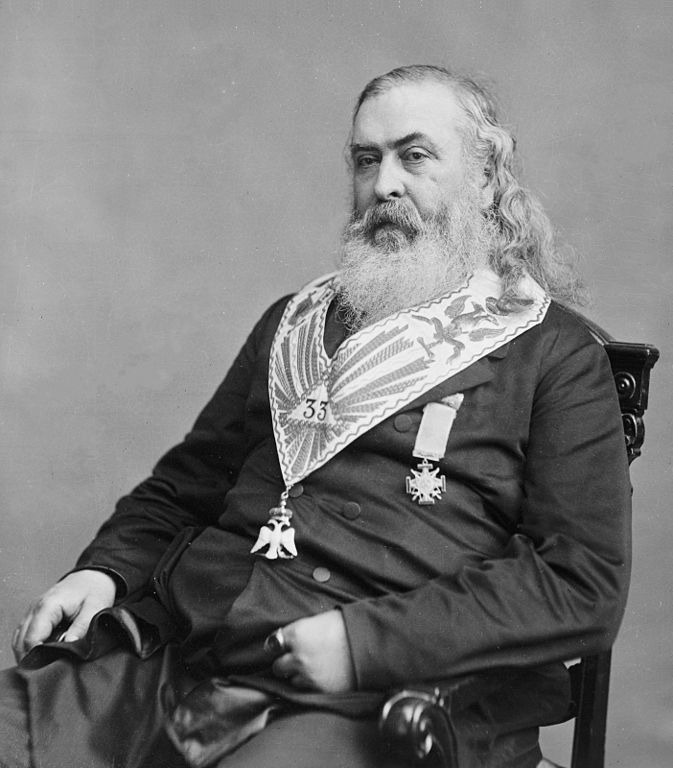

Albert Mackey – Masonic author and scholar

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The subject of the length of a cable tow was one of the questions for discussion at a National Masonic Convention held in the City of Baltimore, USA, in the year 1842.

Albert Mackey says that after considerable discussion on the matter of definition of ‘the scope of man’s reasonable ability’ was arrived at:

…according to the ancient laws of Freemasonry, every brother must attend his Lodge if he is within the length of his cable tow.

The old writers define the length of a cable tow, which they sometimes called a cable’s length, to be three miles for an Entered Apprentice.

But the expression is really symbolic, and as it was defined by the Baltimore Convention in 1842, means the scope of a man’s reasonable ability.

Albert Pike

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

In practical terms Albert Pike saw in it nothing but a physical device for managing the candidate.

In Masonry the physical restraint of the cable tow indicates that the candidate is in submission to the Master. In early Roman times citizens appeared before their monarchs with a rope around their neck to indicate their loyalty to him.

The cable tow is removed from the candidate as soon as he assumes the spiritual bond of the obligation. However, never the means has been made by which to cut the obligation which binds a man spiritually to his Mother Lodge and to the Craft.

Expulsion does not relieve the Mason from his obligation; if the Brother is unaffiliated it does not dissolve the tie; demitting and joining another Lodge can not make the new Lodge his Mother Lodge.

The earlier ‘unknown’ author went on to say:

The old writers define the length of a cable-tow, which they sometimes call a ‘cables length,’ variously.

Some say it is seven hundred and twenty feet, or twice the measure of a circle. Others say that the length of the cable-tow is three miles.

But such figures are merely symbolical, since in one man it may be three miles and in another it may easily be three thousand miles – or to the end of the earth.

For each Mason the cable-tow reaches as far as his moral principles go and his material conditions will allow.

Of that distance each must be his own judge, and indeed each does pass judgment upon himself accordingly, by his own acts in aid of others.

The term ‘cable’s length’ is a measure of length used at sea defined as being two hundred yards, a tenth of a nautical mile, which is the more likely explanation for the reference in the Craft Initiation ceremony, ‘…a cable’s length from the shore’.

Why ‘three’ (miles) as the consensus suggests? Immediately the mind turns to the size of encampments, villages, and towns in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and a natural assumption is that this was a likely footprint of a community and its environs.

With transport on foot or by horse this could be a reasonable assumption, beyond which the individual was excused the duties lain upon others of nearer domicile.

However, the actuality is far simpler and mathematical.

In actuality the horizon is the apparent line that separates earth from sky, the line that divides all visible directions into two categories: those that intersect the Earth’s surface, and those that do not.

At many locations, the true horizon is obscured by trees, buildings, mountains, etc., and the resulting intersection of earth and sky is called the visible horizon, including the effect of atmospheric refraction.

The horizon is the apparent line that separates the surface of a celestial body from its sky

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The approximate distance to the horizon from an observer who is close to the Earth’s surface is:

With d in miles and h in feet. Thus:

For an observer on the ground with eye level at h = 5 ft 7 in (5.583 feet), the horizon is at: 3.1 milesHowever, for an observer standing on a hill 100-feet in height, the horizon is at: 13.2 miles

and for an observer on the summit of a mountain e.g. (22,841 feet in height), the sea-level horizon to the west is at a distance of 200 miles.

From the eighteenth century until the mid twentieth century, the territorial waters of the British Empire, the United States, France and many other nations were three nautical miles (5.6 km) wide.

Originally, this was the length of cannon shot, hence the portion of an ocean that a sovereign state could defend from shore and the distance a man on the shore could see to the horizon.

However, other European countries claimed different distances ranging from two nautical miles to six nautical miles depending on their geography.

During incidents such as nuclear weapons testing and fisheries disputes some nations arbitrarily extended their maritime claims to as much as fifty or even two hundred nautical miles.

Since the late 20th century, the ‘12-mile limit’ has become almost universally accepted. The United Kingdom extended its territorial waters from three to twelve nautical miles (22 km) in 1987.

Conjecture therefore reasons that three miles being Pythagorean is simply the distance an average height person can see to their ‘horizon’ under normal circumstances at sea level.

So, the need to attend lodge is incumbent on every Mason within the ‘totality’ of his sight and world view.

Therefore, it follows that everything within his comprehension must be within the length of his cable-tow and allegory remains intact.

Footnotes

References

NOTES:

The writer is pleased to acknowledge source material:

Craft Rituals – Degree of Initiation

Holy Royal Arch Ritual

Short Talk Bulletin – Vol. IV March 1926 No. 3 By: Unknown

Mackey’s Encyclopaedia of Freemasonry

Wikipedia – Territorial Waters – Diagrams & Pics

Article by: Paul Gardner

Paul was Initiated into the Vale of Beck Lodge No 6283 (UGLE) in the Province of West Kent, England serving virtually continuously in Office and occupying the WM Chair on three occasions.

Paul joined Stability Lodge No 217 in 1997 (UGLE) and now resides with Kent Lodge No 15, (UGLE) the oldest Atholl Lodge with continuous working since 1752, where he was Secretary and now Assistant Secretary and archivist, having been WM in 2002.

In Holy Royal Arch he is active in No 15 Chapter and Treasurer of No 1601, which was the first UGLE Universities Scheme Chapter in 2015.

He was Secretary of the Association of Atholl Lodges which maintains the heritage of the remaining 124 lodges holding ‘Antients’ Warrants and has written a book on Laurence Dermott. - https://antients.org

An Encyclopedia of Freemasonry

By: Albert G. Mackey

Volume one of two volumes. Albert Mackey’s “An Encyclopedia of Freemasonry” is one of the most significant and well-known of Masonic works.

Its usefulness and aid to Masonic students worldwide has been the cornerstone of its popularity since it was first published in 1873.

This photographic reproduction of the 1916 Edition was revised and expanded by William J. Hughan & Edward L. Hawkins and includes a 2015 Foreword by Michael R. Poll. This is a must-have work for all students of Freemasonry.

The Symbolism of Freemasonry

By: Albert G. Mackey

Of the various modes of communicating instruction to the uninformed, the Masonic student is particularly interested in two; namely, the instruction by legends and that by symbols. It is to these two, almost exclusively, that he is indebted for all that he knows, and for all that he can know, of the philosophic system which is taught in the institution.

All its mysteries and its dogmas, which constitute its philosophy, are entrusted for communication to the neophyte, sometimes to one, sometimes to the other of these two methods of instruction, and sometimes to both of them combined.

The Freemason has no way of reaching any of the esoteric teachings of the Order except through the medium of a legend or a symbol.

A legend differs from an historical narrative only in this—that it is without documentary evidence of authenticity. It is the offspring solely of tradition. Its details may be true in part or in whole. There may be no internal evidence to the contrary, or there may be internal evidence that they are altogether false.

But neither the possibility of truth in the one case, nor the certainty of falsehood in the other, can remove the traditional narrative from the class of legends.

More…..

Masonry Dissected

By: Samuel Pritchard

This scarce antiquarian book is a facsimile reprint of the original. Due to its age, it may contain imperfections such as marks, notations, marginalia and flawed pages.

Because we believe this work is culturally important, we have made it available as part of our commitment for protecting, preserving, and promoting the world’s literature in affordable, high quality, modern editions that are true to the original work.

Recent Articles: by Paul Gardner

Exchanged the Sceptre for the Trowel Explore the intriguing history of Royals and Freemasonry following the new Monarch's Coronation. From Prince Albert's initiation to the influence of George II and beyond, discover why royalty has long exchanged the sceptre for the trowel, shaping society and maintaining power through this ancient craft. |

Unearth the mystic origins of Freemasonry in 'That He May Be Crafted.' Paul Gardner explores the symbolic use of working tools from the earliest days of this secret society, revealing a time when only two degrees existed. Delve into this fascinating study of historical rituals and their modern relevance. |

Paul Gardner looks to a time when politics and Masonry were not precluded, but shush! This was London Masons and the Spitalfields Act of 1773-1865. |

That rank is but the guinea’s stamp, the man himself’s the gold. But what does this mean, even given the lyric and tone of Burns’ time? It is oft times used in a derogatory sense, (somewhat in good humour) between Masons (or not) on the achieving of honours. But its antecedents are much more complex than that. |

John and Timothy Coleman Blanchflower were initiated in Walpole Lodge, No. 1500, Norwich England on 2 December 1875; noted as a purveyor of ‘sauce’ to masons! |

Jacob’s Ladder occupies a conspicuous place among the symbols of Freemasonry being on the First Degree Tracing Board, the most conspicuous and first seen by the candidate on his initiation – a vision of beauty and intrigue for the newly admitted. |

During a detective hunt for the owner of a Masonic jewel, Paul Gardner discovered the extraordinary life of a true eccentric: Dr William Price, a Son of Wales, and a pioneer of cremation in Great Britain. Article by Paul Gardner |

Paul Gardner tells the story of his transition from one rule book to another – from the Book of Constitutions to the Rule Book for Snooker! |

Due or Ample Form? What is ‘Ample’ form, when in lodges the term ‘Due’ form is used? |

The Butcher, the Baker, the Candlestick Maker Paul Gardner explores the Masonic link between provincial towns’ craftsmen, shop keepers and traders in times past. Many remain in the modern era and are still to be found on the high street. |

Masonic dining and banquets, at least for the annual Investitures, were lavish, and Kent Lodge No. 15, the oldest Atholl lodge with continuous working from 1752, was no exception. |

The ‘cable-tow’ or ‘noose’ is used in Craft Masonry as part of the ritual, as are ropes and ties in other degrees - but what does it symbolise? |

Paul Gardner reflects on those days of yore and the “gentleman footballer” in Masonry |

What is the Masonic connection with the 1914 Christmas Mary Tin |

That Takes the Biscuit - The Patriot Garibaldi Giuseppe Garibaldi Italian general and politician Freemason and the Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy. |

W.Bro. Paul Gardner looks at a mid 19th century artefact and ponders ‘Chairing’ |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device