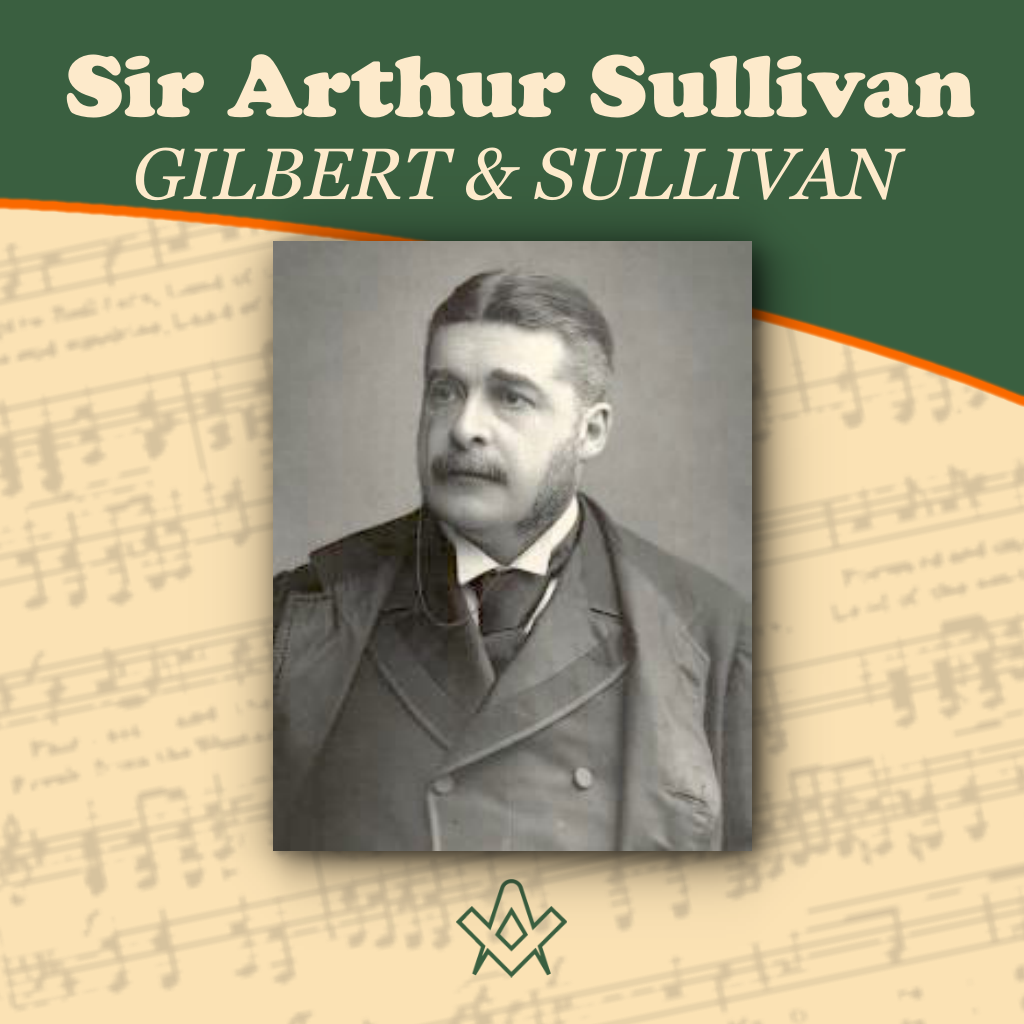

We are all familiar with the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan, but did you know Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan was a Freemason ?

Arthur Seymour Sullivan was born in Lambeth on 13 May 1842. His father, Thomas Sullivan, was an Irish musician and bandmaster at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst.

Young Arthur exhibited great musical talent and could play all the wind instruments in his father’s band by the age of eight.

He was educated at a school in Bayswater until 1854.In April of that year he was accepted as a chorister at the Chapel Royal, under the tutelage of the Revd. Thomas Helmore, even though he was well over the normal age of admission. He was regularly called upon to sing solo works.

In 1855, he became a composer with the publication of the sacred work O Israel. Although the youngest entrant, in 1856 he won a competition for the Mendelssohn Scholarship to study at the Royal Academy of Music.

In 1858, he transferred to the prestigious Conservatorium in Leipzig. His final examination piece was a successful performance of incidental music to Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

In April 1861, he returned to London to become the organist at St. Michael’s Church, Chester Square. In 1862, his incidental music for The Tempest was performed at the Crystal Palace and was received with such acclaim that he was launched into the career of musical composition almost overnight.

Sullivan aged 16, in his Royal Academy of Music uniform

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Arthur Sullivan’s musical career developed steadily with the composition of many songs and hymns, which provided a regular stream of royalties to sustain his living.

His reputation secured him significant appointments such as First Principal of the National Training School of Music, and Organist at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden.

In May 1864, he composed his second major work, the ballet L’Ile Enchantée, and it was also in this year that his masque, Kenilworth, had its première at the Birmingham Festival.

As the years progressed Sullivan composed many works varying from operatic scores for the very successful Box and Cox, sacred choral works, and the music for Onward Christian Soldiers.

He also produced incidental music for a number of theatrical productions, such as The Merchant of Venice (1871) and The Merry Wives of Windsor (1874).

Illustration of Thespis in The Illustrated London News, 6 January 1872

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

In 1871, he began collaboration with William Schwenck Gilbert, on the Christmas production of Thespis at the Gaiety Theatre.

They had been introduced in 1868 by the English singer and composer Frederic Clay. Both of them had an interest in Freemasonry.

Sullivan was initiated into the Lodge of Harmony No. 255, Richmond, Surrey on 11 April 1865, passed on 3 October, and raised on 30 January 1866.

He became a joining member of Studholme Lodge No. 1591, London in 1896.

The United Grand Lodge of England appointed Sullivan to the position of Grand Organist in 1887. He extended his Masonic interest by becoming exalted in Friends in Council Chapter No. 1383, London on 12 July 1887.

In the Ancient and Accepted Rite, he was perfected in Bayard Chapter Rose Croix No. 71, London in 1876. He resigned in 1881.

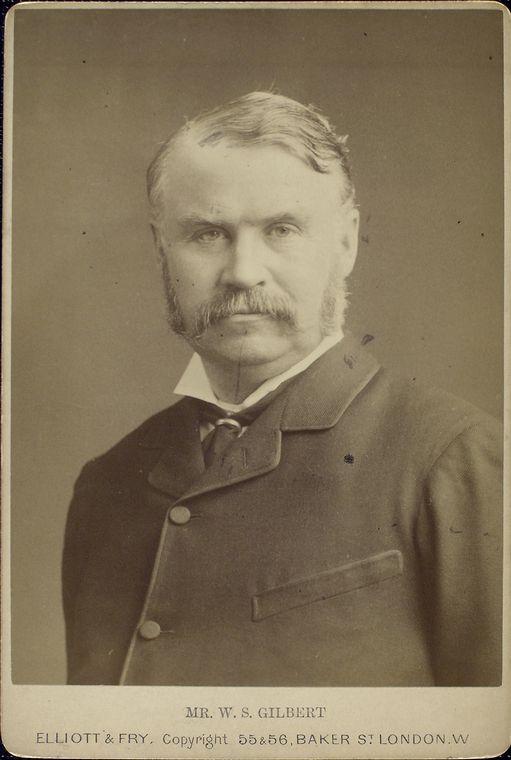

Gilbert was admitted in a Scottish lodge, St. Machar No. 54 in 1871.

In London Gilbert joined Bayard Lodge No. 1615 in June 1876. In February 1877, Gilbert was exalted into Friends in Council Chapter No 1383, a few months before Sullivan joined.

William S. Gilbert

IMAGE LINKED: The New York Public Library Digital Collections Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Their common interest in Freemasonry, and membership of the same Lodges, would have made it much easier for Richard D’Oyly Carte to invite Sullivan to compose music for Gilbert’s libretto for Trial by Jury.

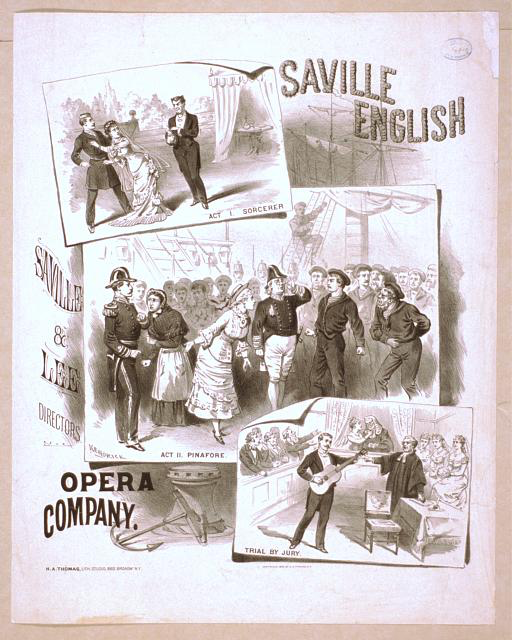

The production was a great success, becoming the starting point for a collaboration that produced fourteen comic operas, including such popular favourites as H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, and The Mikado.

Saville English Opera Company – ‘H.M.S. Pinafore’, ‘Sorcerer’, and ‘Trial by Jury’.

IMAGE LINKED: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Allusions to Freemasonry only appeared in one production, The Grand Duke first performed in March 1896.

Image of Rutland Barrington (Ludwig) and Ilka Palmay (Julia) from the original production of The Grand Duke, 1896.

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

In the libretto Ludwig sings:

By the mystic regulation

Of our dark Association,

Ere you open conversation

With another kindred soul,

You must eat a sausage-roll!

Then the chorus sings: You must eat a sausage-roll!

Ludwig continues:

If, in turn, he eats another,

That’s a sign that he’s a brother

Each may fully trust the other.

It is quaint and it is droll,

But it’s bilious on the whole.

Sullivan and Gilbert became wealthy from the proceeds of their comic operas. D’Oyly Carte became richer than either of them, making enough money to build the Savoy Theatre in 1881, as a venue to stage their productions.

It was the first public building in the world to be lit entirely by electricity. For many years, the Savoy Theatre was the home of the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, which continued to be run by the Carte family for over a century.

He also built the Savoy Hotel, and other luxurious hotels.

Richard D’Oyly Carte By Ellis & Walery, from the 1914 edition of Cellier & Bridgeman’s Gilbert and Sullivan and Their Operas

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Sullivan also continued his work in other fields of music.

In 1880, he was appointed conductor of the Leeds Triennial Festival, writing two of his most famous choral works for it: The Martyr of Antioch and The Golden Legend.

The latter work was so successful that it rivalled Handel’s Messiah in popularity. He also continued writing incidental music for some of Shakespeare’s plays, such as Henry VIII and Macbeth.

It was during this period that he composed the extremely popular song The Lost Chord. The feeling in this work may have been engendered by the fact that he composed it at the time of his brother Frederic’s terminal illness, who died in January 1877.

Fred Sullivan, the composer’s brother c. 1870

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

His compositions brought Sullivan public recognition. He received honorary doctorates from Oxford and Cambridge universities and was knighted for his services to music in 1883.

He was also invited to compose the music for the inaugural opera of the Royal English Opera House in Cambridge Circus, which had been built by D’Oyly Carte for putting on performances of English grand opera.

Sullivan’s score was for a libretto, based on Sir Walter Scott’s novel Ivanhoe written by Julian Sturgis. It was very successful, running for 155 consecutive performances.

Unfortunately, D’Oyly Carte had not commissioned any other British operas, so he was eventually obliged to sell the opera house, though it still exists today as the Palace Theatre.

Left: Caricature of William Gilbert by L. J. Binns

Right: Caricature of Arthur Sullivan by L. J. Binns

IMAGE LINKED: The New York Public Library Digital Collections Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

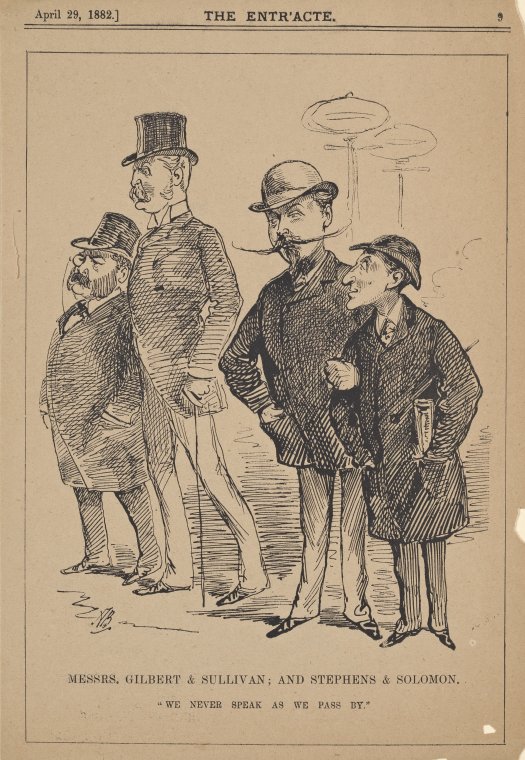

All was not sweetness and light during Gilbert and Sullivan’s collaboration.

Sullivan felt that the comic operas were too repetitive in style, seeking the challenge of more major works.

But it was Gilbert who initiated a challenge to their collaboration with D’Oyly Carte.

In April 1890, during a run of The Gondoliers, Gilbert claimed that D’Oyly Carte had misused funds from the production. In particular, he claimed that D’Oyly Carte had charged the cost of a new carpet, for the lobby of the Savoy Theatre, to the partnership.

Gilbert insisted that this was a maintenance cost that should be paid by D’Oyly Carte. Carte refused to reconsider the accounts, so Gilbert stormed out, writing to Sullivan I left him with the remark that it was a mistake to kick down the ladder by which he had risen.

Helen Carte claimed that Gilbert had spoken to her husband in a manner that would have been unsuitable, even for ticking off an offending servant.

Messrs. Gilbert & Sullivan; and Stephens & Solomon, “We never speak as we pass by”.

IMAGE LINKED: The New York Public Library Digital Collections Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

This spat was really the tip of the iceberg. Underlying Gilbert’s outburst was his concern that D’Oyly Carte could not be trusted with the management of the financial affairs of the partnership.

Gilbert claimed that D’Oyly Carte had made a number of serious blunders with the accounts and might even be suspected of trying to swindle the other two.

On 28 May 1891, Gilbert wrote to Sullivan claiming that D’Oyly Carte had admitted to an unintentional overcharge of almost £1000 for electric lighting.

The dispute rumbled on towards an inevitable court case.

On 1 September 1890, the case of W. S. Gilbert v Richard D’Oyly Carte was heard in the High Court of Justice. Gilbert demanded that the full accounts for The Gondoliers should be scrutinised, and he should receive his full share of the net profits for the second quarter.

He requested that a Receiver should be appointed to protect his future earnings at the Savoy Theatre. D’Oyly Carte agreed to pay Gilbert an additional £1000 for the last quarter, and to provide accurate accounts.

The Judge, however, concurred with Carte’s barristers that a Receiver would cause undue interference with the management of the theatre, and was, thus, not required.

Sullivan supported this argument by swearing an affidavit that there were outstanding legal expenses. Gilbert’s solicitors discovered that, in fact, that these legal expenses had already been paid.

Gilbert wrote to Sullivan asking him to retract his affidavit, but Sullivan refused, causing a rift in their long-term friendship.

Sullivan probably felt that he had to support D’Oyly Carte because the latter was building the Royal English Opera House in which Sullivan hoped his grand opera Ivanhoe would be produced, as it subsequently was.

Meanwhile Gilbert withdrew the performance rights to his libretti and declared that he would not write any future operas for the Savoy Theatre.

Both men continued to follow their professional pursuits. Gilbert wrote the libretto to The Mountebanks and Haste to the Wedding. Sullivan composed the music for Haddon Hall.

Meanwhile D’Oyly Carte was grappling with the financial problems resulting from his failed project with the Royal English Opera House.

He realised that the rift between Gilbert and Sullivan had resulted in this, erstwhile, harmonious pair of geese no longer laying any golden financial eggs for him.

Carte and his wife set about trying to patch things up between Gilbert and Sullivan.

At first, they had no success, but then, in late 1891, Gilbert and Sullivan’s music publisher, Tom Chappell, stepped in as peacemaker, successfully bringing his very profitable artists together again.

Richard D’Oyly Carte, W. S. Gilbert, and Arthur Sullivan together again for Utopia, Limited, after a long quarrel. – Alfred Bryan (1852-99) – 1894 Entr’acte Annual.

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The reunited pair produced Utopia Limited as a Savoy opera. The libretto satirises limited liability companies, particularly the concept that a bankrupt company could leave creditors unpaid without any liability on its part.

It opened on 7 October and ran for 245 performances but did not match the success of earlier operas.

Despite the contemporary resonance of the satire, it is rarely performed in modern times, possibly because of the costs in mounting a production, and the obscurity of some of the plot detail.

Nevertheless, George Bernard Shaw wrote a glowing review at the time, claiming it was one of the best Gilbert and Sullivan operas he had seen.

The Grand Duke or The Statutory Duel was the final collaboration of Gilbert and Sullivan. As previously mentioned, it was the only one of their operas that contained Masonic references. It was premiered at the Savoy Theatre on 7 March 1896, running for 123 performances.

Although it had a good initial reception, the production was not a success, and turned out to be the only financial failure of the partnership.

So, their collaboration had come to an end, like a brilliant firework display that inevitably fizzles out until all is darkness.

Arthur Sullivan continued to compose with other librettists, but the works did not rise to the standard he had achieved with Gilbert.

However, in 1899, Sullivan collaborated with Basil Hood, achieving a good reception for The Rose of Persia. Sullivan’s musical reputation was well established, so he was frequently called upon to compose music for royal or state occasions.

He was commanded to set the Jubilee Hymn to music for part of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee celebrations in 1897.

He also composed music for the ballet Victoria and Merrie England, which depicted Britain’s greatness in a series of tableau.

It was a great success and ran for six months at the Alhambra Theatre.

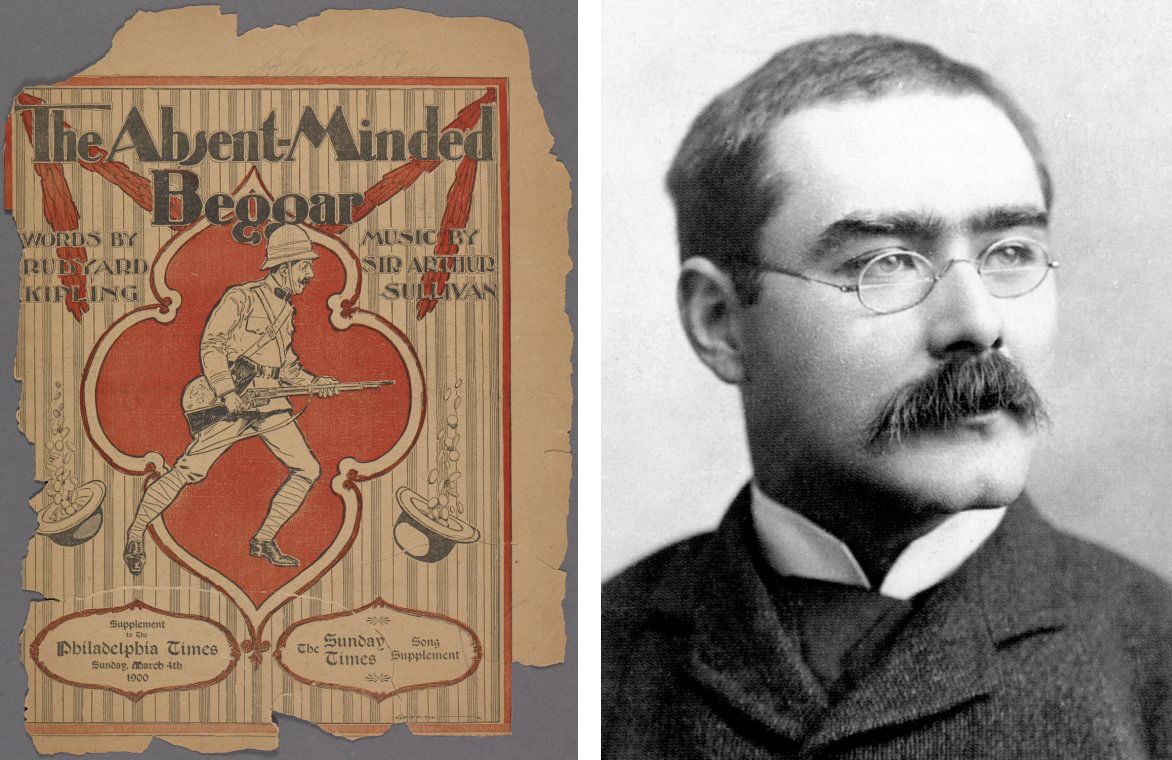

In November 1899, he set music to Rudyard Kipling’s The Absent-Minded Beggar, which was part of a Daily Mail fund raising exercise to support the wives and families of soldiers serving in the Boer War.

The fund was the first such charitable effort for a war.

Left: The Absent-Minded Beggar – Arthur Sullivan’s collaboration with Rudyard Kipling (a fellow Freemason) The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Right: Portrait of Rudyard Kipling by Elliott Fry, from the biography Rudyard Kipling by John Palmer – wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The chorus of the song exhorted its audience to “pass the hat for your credit’s sake and pay– pay– pay!”

The poem and song caused an overwhelming patriotic response throughout the nation and was performed throughout the war.

Kipling was offered a knighthood shortly after publication but declined the honour.

The publication of the poem, and associated sheet music raised £250,000 for the fund.

Arthur Sullivan completed his final work in 1900. It was commissioned by the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral, and consisted of a setting of the Te Deum Laudamus (also known as Boer War Te Deum) intended to commemorate the expected British Victory in the Boer War.

He was working on an opera with Basil Hood in the summer of 1900, but his health rapidly declined to such an extent that he died on 22 November, very appropriately the feast day of St Cecilia, the patron saint of music.

Sullivan had wished to be buried with his parents in Brompton cemetery, but this was overruled by Queen Victoria who insisted that he should be buried in St Paul’s Cathedral.

The funeral arrangements were more like those for a state funeral.

The burial service started in the Chapel Royal, St James where Sullivan had begun his musical career as a choir boy.

Many people gathered at the lower end of St James Street, and the west end of Pall Mall to pay their respects to the departed musician.

The chapel was decorated with flowers. White lilies and chrysanthemums were placed on the altar, in front of which had been placed a floral lyre made from mauve orchids.

Many notable people were present amongst the mourners, as well as individuals who had worked with Sullivan.

The coffin was covered with beautiful flowers, including a wreath from the Queen, wreaths from members of the nobility and Sullivan’s family.

After the service the coffin was conveyed by hearse through the streets to St Paul’s. Members of the public lined the route of the procession.

The cathedral was packed with mourners. Music was provided by the band of the Scots Guards and the cathedral organ.

Among the distinguished guests was Mr Hermann Klein representing Grand Lodge. Funeral marches by Chopin, Mendelssohn and Beethoven were played.

The coffin was placed on a catafalque beneath the dome. Immediately below this was a wide opening in the floor of the nave to enable the coffin to be lowered into the crypt.

![]()

His sun is gone down while yet it was day…

White chrysanthemums bordered the opening, and a floral inscription in violets read simply: His sun is gone down while yet it was day. At the close of the service the full company and chorus of the Savoy Theatre sang the hymn “Brother, thou art gone before us”, from Sullivan’s The Martyr of Antioch.

Memorial To Sir Arthur Sullivan, Victoria Embankment Gardens, London. Photo taken by lonpicman

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Gilbert survived Sullivan by some years, but his ending was a tragic accident. On 29 May 1911, Gilbert was about to give a swimming lesson to two girls in the lake at his home, Grim’s Dyke.

One of the girls got into difficulties and called for help. Gilbert dived into the water to save her but suffered a fatal heart attack in the middle of the lake.

His Foe was Folly and his Weapon Wit…

He was 74 at his death. He was cremated at Golders Green, and his ashes buried in the churchyard at St John’s, Stanmore.

An inscription on the south wall of the Thames Embankment reads: His Foe was Folly and his Weapon Wit.

Memorial to W. S. Gilbert on Victoria Embankment, London. Near Embankment Pier. Photo: lonpicman

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Article by: Nigel Wade

Educated at The Stationers’ Company's School, and the University of London.

A regular writer for the school magazine and ‘The Old Stationer’; member of the Brentwood Writers’ Circle.

Nigel has written one children's book ‘City Fox’, and various articles for ‘The Square Magazine’.

The Complete Annotated Gilbert & Sullivan: 20th Anniversary Edition

By: Ian Bradley (Author)

Ian Bradley’s Complete Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan has established itself across the world as the authorized and definitive ‘Bible’ for all those interested in the Savoy operas.

Originally published in two Penguin paperbacks in the 1980’s, a single-volume comprehensive compendium, hailed widely as “easily the best annotated Gilbert & Sullivan available” (Gayden Wren, New York Times) was published by Oxford University Press in 1996. This brand new 20th anniversary edition includes Thespis, Gilbert and Sullivan’s first collaboration which is now being increasingly performed, despite the loss of the vocal and orchestral scores.

It also features a completely new introduction, reflecting on the state of Gilbert and Sullivan nearly 150 years after the pair began their legendary collaboration, and new annotations addressing recent performance history, newly discovered ‘lost’ songs and dialogue, and, for the first time, Gilbert and Sullivan references in contemporary popular culture.

Scholars, performers, and fans are sure to rejoice in this indispensable companion to the Gilbert and Sullivan repertoire, newly updated for the present day.

The Topsy Turvy World of Gilbert and Sullivan

By: Keith Dockray (Author), Alan Sutton (Author)

No musical partnership has enjoyed greater success during its time span, or bequeathed a more powerful and enduring legacy, than that of Gilbert and Sullivan in the later nineteenth century.

Even before their first successful collaboration in 1875, both William Schwenk Gilbert (1836-1911) and Arthur Seymour Sullivan (1842-1900) had already forged considerable reputations for themselves.

Thereafter, between 1877 and 1896, Gilbert wrote the librettos, and Sullivan the music, for no fewer than a dozen Savoy operas, among them the still regularly performed ‘H.M.S. Pinafore’ (1878), ‘The Pirates of Penzance’ (1879), ‘Iolanthe’ (1882), ‘The Mikado’ (1885), ‘The Yeomen of the Guard’ (1888) and ‘The Gondoliers’ (1889).

Not only are the plots ingenious, the lyrics witty and the music compelling, the operas also present modern audiences with splendidly rich and satirical evocations of Victorian England and its society: the prime subject matter of this book!

Recent Articles: in people series

Celebrate the extraordinary legacy of The Marquis de La Fayette with C.F. William Maurer's insightful exploration of Lafayette's 1824-25 tour of America. Discover how this revered leader and Freemason was honored by a young nation eager to showcase its growth and pay tribute to a hero of the American Revolution. |

Albert Mackey and the Civil War In the midst of the Civil War's darkness, Dr. Albert G. Mackey, a devoted Freemason, shone a light of brotherhood and peace. Despite the nation's divide, Mackey tirelessly advocated for unity and compassion, embodying Freemasonry's highest ideals—fraternal love and mutual aid. His actions remind us that even in dire times, humanity's best qualities can prevail. |

Discover the enduring bond of brotherhood at Lodge Dumfries Kilwinning No. 53, Scotland's oldest Masonic lodge with rich historical roots and cultural ties to poet Robert Burns. Experience rituals steeped in tradition, fostering unity and shared values, proving Freemasonry's timeless relevance in bridging cultural and global divides. Embrace the spirit of universal fraternity. |

Discover the profound connections between John Ruskin's architectural philosophies and Freemasonry's symbolic principles. Delve into a world where craftsmanship, morality, and beauty intertwine, revealing timeless values that transcend individual ideas. Explore how these parallels enrich our understanding of cultural history, urging us to appreciate the deep impacts of architectural symbolism on society’s moral fabric. |

Discover the incredible tale of the Taxil Hoax: a stunning testament to human gullibility. Unmasked by its mastermind, Leo Taxil, this elaborate scheme shook the world by fusing Freemasonry with diabolical plots, all crafted from lies. Dive into a story of deception that highlights our capacity for belief and the astonishing extents of our credulity. A reminder – question everything. |

Dive into the extraordinary legacy of Alexander Von Humboldt, an intrepid explorer who defied boundaries to quench his insatiable thirst for knowledge. Embarking on a perilous five-year journey, Humboldt unveiled the Earth’s secrets, laying the foundation for modern conservationism. Discover his timeless impact on science and the spirit of exploration. |

Voltaire - Freethinker and Freemason Discover the intriguing connection between the Enlightenment genius, Voltaire, and his association with Freemasonry in his final days. Unveil how his initiation into this secretive organization aligned with his lifelong pursuit of knowledge, civil liberties, and societal progress. Explore a captivating facet of Voltaire's remarkable legacy. |

Robert Burns; But not as we know him A controversial subject but one that needs addressing. Robert Burns has not only been tarred with the presentism brush of being associated with slavery, but more scaldingly accused of being a rapist - a 'Weinstein sex pest' of his age. |

Richard Parsons, 1st Earl of Rosse Discover the captivating story of Richard Parsons, 1st Earl of Rosse, the First Grand Master of Grand Lodge of Ireland, as we explore his rise to nobility, scandalous affiliations, and lasting legacy in 18th-century Irish history. Uncover the hidden secrets of this influential figure and delve into his intriguing associations and personal life. |

James Gibbs St. Mary-Le-Strand Church Ricky Pound examines the mysterious carvings etched into the wall at St Mary-Le-Strand Church in the heart of London - are they just stonemasons' marks or a Freemason’s legacy? |

Freemasonry and the Royal Family In the annals of British history, Freemasonry occupies a distinctive place. This centuries-old society, cloaked in symbolism and known for its masonic rituals, has intertwined with the British Royal Family in fascinating ways. The relationship between Freemasonry and the Royal Family is as complex as it is enduring, a melding of tradition, power, and mystery that continues to captivate the public imagination. |

A Man Of High Ideals: Kenneth Wilson MA A biography of Kenneth Wilson, his life at Wellington College, and freemasonry in New Zealand by W. Bro Geoff Davies PGD and Rhys Davies |

In 1786, intending to emigrate to Jamaica, Robert Burns wrote one of his finest poetical pieces – a poignant Farewell to Freemasonry that he wrote for his Brethren of St. James's Lodge, Tarbolton. |

Alex Lishanin explores Mumbai and discovers the story of Lodge Rising Star of Western India and Manockjee Cursetjee – the first Indian to enter the Masonic Brotherhood of India. |

Aleister Crowley - a very irregular Freemason Aleister Crowley, although made a Freemason in France, held a desire to be recognised as a 'regular' Freemason within the jurisdiction of UGLE – a goal that was never achieved. |

Sir Joseph Banks – The botanical Freemason Banks was also the first Freemason to set foot in Australia, who was at the time, on a combined Royal Navy & Royal Society scientific expedition to the South Pacific Ocean on HMS Endeavour led by Captain James Cook. |

Making a Mason in Prison: the John Wilkes’ exception? |

"To be a good man and true" is the first great lesson a man should learn, and over 40 years of being just that in example, Dr Buck won the right to lay down the precept. |

Elias Ashmole: Masonic Hero or Scheming Chancer? The debate is on! Two eminent Masonic scholars go head to head: Yasha Beresiner proposes that Elias Ashmole was 'a Masonic hero', whereas Robert Lomas posits that Ashmole was a 'scheming chancer'. |

Sir Arthur Sullivan - A Masonic Composer We are all familiar with the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan, but did you know Sullivan was a Freemason, lets find out more…. |

The Much-Maligned Dr John Misaubin The reputation of the Huguenot Freemason, has been buffeted by waves of criticism for the best part of three hundred years. |

Was William Morgan really murdered by Masons in 1826? And what was the lie Masonic author Rob Morris told? Find out more in the intriguing story of 'The Morgan Affair'. |

Lived Respected - Died Regretted Lived Respected - Died Regretted: a tribute to HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh |

Who was Moses Jacob Ezekiel, a Freemason, American Civil War Soldier, renowned sculptor ? |

A Masonic author and Provincial Grand Master of Forfarshire in Scotland |

Who was Philip, Duke of Wharton and was he Freemasonry’s Loose Cannon Ball ? |

Richard Carlile - The Manual of Freemasonry Will the real author behind The Manual of Freemasonry please stand up! |

Nicholas Hawksmoor – the ‘Devil’s Architect’ Nicholas Hawksmoor was one of the 18th century’s most prolific architects |

By Bro. Anthony Oneal Haye (1838-1877), Past Poet Laureate, Lodge Canongate Kilwinning No. 2, Edinburgh. |

The Curious Case of the Chevalier d’Éon A cross-dressing author, diplomat, soldier and spy, the Le Chevalier D'Éon, a man who passed as a woman, became a legend in his own lifetime. |

Mozart Freemasonry and The Magic Flute. Rev'd Dr Peter Mullen provides a historical view on the interesting topics |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device

Tubal Cain

Masonic Aprons NFT

Each Tubal Cain Masonic Apron NFT JPEG includes a full size masonic apron and worldwide shipping