Elias Ashmole. Masonic Hero or Scheming Chancer?

A Hard Look at the Evidence

Elias Ashmole is well known to all Freemasons because of the many Masonic myths about him.

For example, a little leaflet, ‘Your Questions Answered’ (issued by the United Grand Lodge of England in 1999) proudly, but wrongly, claims; ‘The earliest recorded making of a Freemason in England is that of Elias Ashmole in 1646’. In fact, the first documented Freemasonic initiation on English soil happened in 1641, at Newcastle, and that Freemason was Bro Sir Robert Moray.

How and why Ashmole came to be ‘made a Mason’ at Warrington, is a more curious question. In my view his motives were far more political than many modern Masons seem to believe.

Elias Ashmole. Line engraving, 1747, after W. Faithorne..

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection – Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

He was born in Lichfield on 23 May 1617, the only child of the local saddler.

He went on to become both a solicitor and an astrologer and wrote a well-respected book on the Order of the Garter.

Today he is best known to the public for the Ashmolean Museum. When he died in 1692, having no children despite being married three times, he left his library and his collection of antiquities to Oxford University.

This bequest founded the museum and his reputation as a benefactor of science.

At the age of sixteen young Elias left Lichfield to move to London, to live with Baron James Paget, his mother’s cousin by marriage.

There, he started to keep a diary. It is from that diary I discovered many disturbing facts about him.

In 1638, he qualified as a solicitor and married Eleanor Manwaring, a young lady from Smallwood, near Warrington, whom he met at the Paget’s house.

Eleanor was an elderly spinster, 14 years older than Ashmole, he was 21 she was 35. She died, from the complications of pregnancy on 6 December 1641, leaving Ashmole with a small private income.

She had gone to Smallwood to stay with her parents for the birth and Elias only learned of her death when he travelled up to Cheshire, intending to spend Christmas with her and his in-laws.

In August the following year, he moved to Smallwood to live with his father-in-law, Peter Manwaring, to get away from the political unrest in London.

He worked as a solicitor during this stay in Cheshire, occasionally traveling back to London to assist Henry Manwaring, his late wife’s cousin, on legal business. Ashmole’s diary shows his strong Royalist sympathies.

On 27 May 1643, he travelled to Oxford having been appointed to collect the King’s Excise from the town of Lichfield. Charles I had been driven out of London and had established his Court in Oxford.

Ashmole took the opportunity become a ‘stranger’ or casual student at Brasenose College to stay in the city.

He attended lectures on natural philosophy, mathematics, astronomy and astrology but did not take a degree.

On 22 Mar 1645, he met Captain Wharton, an officer in the King’s garrison and a keen astrologer.

Within a month Wharton appointed him as one of the four Masters of Ordinance for the city.

Sir George Wharton. Line engraving

IMAGE LINKED: welcome collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

After Charles I’s defeat at Naseby, the king returned to Oxford, staying from 28 to 30 August before leaving the city to its fate.

Ashmole worked on the defences against the expected Parliamentary attack but managed to get out before the city fell.

He secured the position of King’s Commissioner of Excise in Worcester and was sworn in on 27 December 1645. He lost no time in ingratiating himself with the local bigwigs, dining with Lords Bereton and Astley.

He proudly records in his diary that he has also met Sir Gilbert Gerard, the Royalist Governor of Worcester. He quickly became involved in assisting Lord Astley to prepare his forces to relieve Chester.

Ashmole continually cast horoscopes to predict the course of the war and its likely consequences.

He was also interpreted his dreams to foretell the future. On 27 April, he recorded that had dreamed: ‘The King went from Oxf: in disguise to ye Scotts.’ [This is one of the few accurate astrological predictions he made, as Charles did go in disguise to Newark where he surrendered to the Covenantors, who promptly sold him to Oliver Cromwell.]

King Charles I giving orders to Sir Edward Walker during the English Civil War. Engraving, 1705..

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection – Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Ashmole was closely immersed in the Royalist cause. He bought fashionable outfits to impress his sponsors, and various ladies, he met.

On 22 May 1646, Lord Astley commissioned him as a Captain in the Worcester regiment. Oxford fell on 20 June, leaving only Lichfield and Worcester standing.

Ashmole’s diary recorded the fall of Lichfield on 14 July 1646 and ten days later he wrote ‘Worcester was surrendered; and thence I ride out of Towne according to the Articles, and I went to my Father Manwarings in Cheshire.’

This is confirmed by the Calendar of State Papers where Captain Ashmole is listed among the surrendered officers.

Worcester was the last garrisoned town to hold out for the King and its fall signalled the end for Charles I.

As a surrendered Royalist, Ashmole was forbidden to live within the bounds of the city of London and so was unable to practice law.

He returned to the home of his dead wife’s father in Cheshire because he had nowhere else to go. He had picked the wrong side of the civil war and by late 1646 was out of a job and of political favour.

Small wonder that he kept casting horoscopes to see if his luck would improve and plotted how he might safely travel to London to perhaps marry a wealthy widow.

Almost any wealthy widow would have done. Mrs Cole, Mrs Minshull, Mrs Ireland, Mrs Thornborough, Mrs March, Lady Fitton, or Lady Mainwaring all figure in the erotic, and pecuniary dreams that the twenty-nine-year-old Ashmole recorded during this period.

His diary entries show him to be an inconsiderate and outrageous flirt, as he tries to consummate a speedy marriage to help fill his ‘leane Purse’.

Elias Ashmole’s house. Engraving after R. B. Schnebbelie, 1815..

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection – Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Here are some examples of entries about his dalliances with Lady Bridget Thornborough, Mrs Wall and finally Mrs March, none of whom would consent to marry him.

‘The Lady Thornborough sent for me and I went to her and found her in bed.’

‘Mrs Thornborough lay upon a bed with me and exercised some love to me and that she did really love me. I felt her {c***} and it seemed to be closed up.’

‘This night from 10 to almost 12; I discoursed with Mrs Wall in her bedchamber where still all her discourse beat upon her fear that she should not marry to please her friends.’

{Writing of Mrs March who had consented to ‘come undressed’ to him while he was still in bed} ‘I had this day divers kisses from her and she lent me her picture to wear next to my heart.

She then put her hand into bed to me and protested she had never done so much since her husband died and she told me she hoped I was confident there was nothing she could afford me but I might command it.’

Despite his romantic efforts, Ashmole did not persuade any of these wealthy widows to marry him, so he had to consider other means of making his living.

The Articles of Surrender he had signed obliged him to either return to his home or ‘go overseas and never to ‘beare Armes’ any more against the Parliament of ‘England or do anything wilfully to the prejudice of their affaires’.

His mother died while he was besieged in ‘Worcester. Wealthy Lady Thornborough had refused his offer of marriage and his only remaining family was his father-in-law father, Mr Peter Manwaring of Smallwood, ‘Cheshire.

He ‘scratched a living carrying out simple legal duties for his father-in-law but became highly stressed.

On 16 September 1646, he was feeling very sorry for himself. He started to develop boils on his arms and then things got worse.

He confided to his diary:

‘this night I first perceived a boyl to rise upon my arse’.

His joints ached, he was extremely constipated and became so concerned that he started to record the number of stools he passed each day.

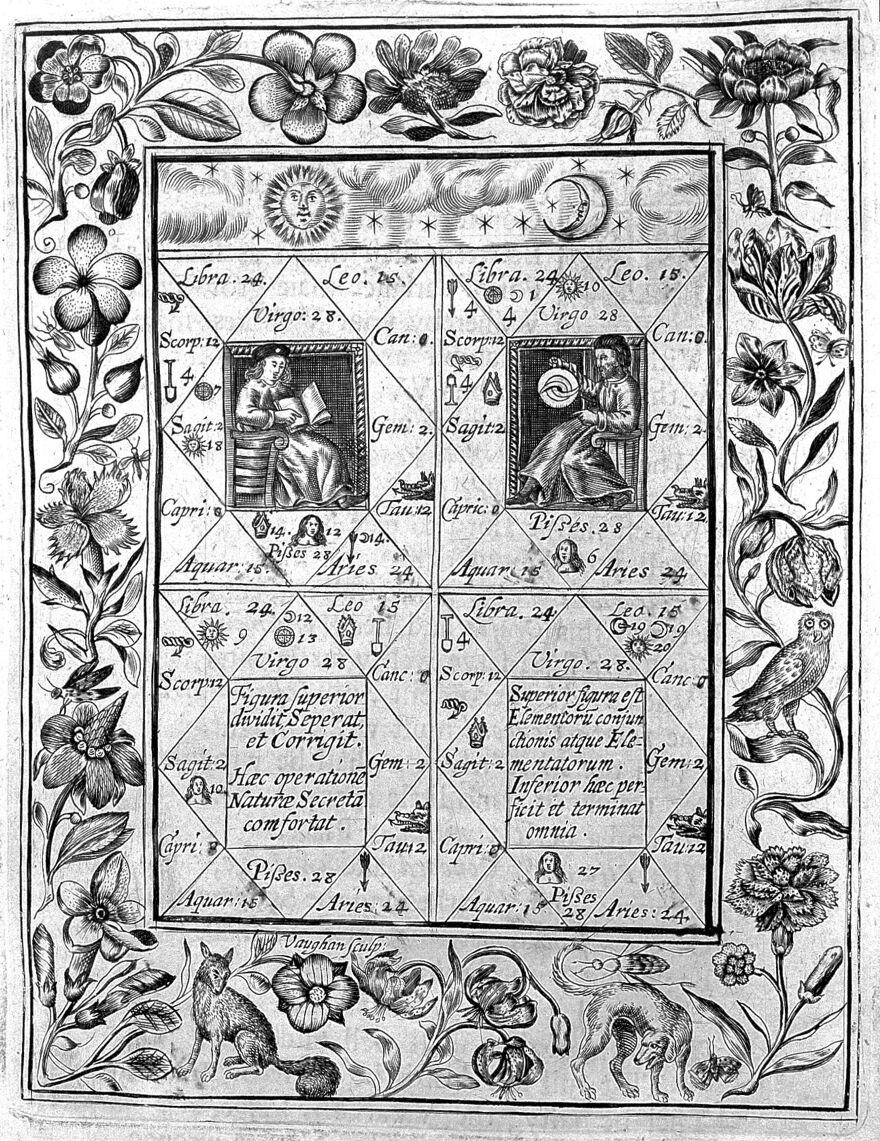

E. Ashmole, Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum.

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection – Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

He continually cast new horoscopes asking if he should ‘get a fortune by a wife without pains and easily’.

Though what rich widow would want a constipated outcast with an enormous boil on his backside, is a question he avoided asking the stars.

Young Ashmole was certainly ambitious and not shy of currying favour if he thought it could help his fortunes.

Then he resolved the question of what to do. On 17 October 1646, he borrowed money from his cousin, Col Henry Manwaring, and bought a horse from Congleton Horse Fair.

On 20 October he gathered his possessions together and by 25 October was on his way to London, despite the undertaking he had given at Worcester not to live in the capital.

He evidently believed that he would now be allowed to ignore the restraining order he had received at the surrender of the city.

By 20 November 1646, he was living in London and mixing freely with astrologers, alchemists and mathematicians.

Among these was William Lilly, who was a well-established astrologer, writer of a much-respected University textbook on Christian Astrology and a strong supporter of Parliament.

What had happened to change Ashmole’s fortunes and make him acceptable to such a man?

The difference was that his cousin, Col Henry Manwaring, had introduced Ashmole to a Lodge of Freemasons, meeting in Warrington.

He had been made a Mason on the afternoon of 16 October 1646. His membership of the Craft was the key to meeting many influential people and allowing him to move to London despite the law.

Indeed, a note in the papers of the Public Record Office, State Papers Domestic, Interregnum A. confirms the unlawful nature of his move to London when it says: ‘He (Ashmole) doth make his abode in London notwithstanding the Act of Parliament to the Contrary.’

Ashmole went from despairing outcast, suffering from constipation, aching joints, repeated failures in love and boils on his bum, to an enthusiastic and bold adventurer who was accepted in London Parliamentarian society.

But he was now a Freemason and I suspect he became a Freemason to open doors for him at the highest levels in Parliamentary London.

Unfortunately, his diary entry only confirms where and with whom he became a Mason. It does not explain why wanted to join the Craft.

His diary entry for 16 October 1646, reads:

‘4H.30’ P.M. I was made a free Mason at Warrington in Lancashire, with Coll: Henry Mainwaring of Karincham in Cheshire. The names of those that were then of the Lodge, Mr: Rich Penket Warden, Mr: James Collier, Mr: Rich: Sankey, Henry Littler, John Ellam, Rich: Ellam & Hugh Brewer.’

The men making up the lodge are mainly local landowners, who would have been well known to the Manwaring family.

What is noticeable about the membership of this Lodge is that they are drawn from both sides of the Civil War.

A Roundhead Colonel and two Royalist Captains as well as the local landowners from Warrington, Newton-le-Willows and Lymm, whose politics I don’t know.

Ashmole was revitalised, he stopped drifting and immediately moved back to London.

His diary entries show he had been afraid to contemplate such a move before his initiation.

Had he acquired a list of useful Parliamentary contacts in London and now knew how to identify himself to them?

Ashmole’s biographer, C H Josten, says of this time:

‘Perhaps his newly acquired Masonic connections had influenced Ashmole’s decision.

Certainly, on his return to London, his circle of friends soon included many new acquaintances among astrologers, mathematicians, and physicians whose mystical leaning might have predisposed them to membership of speculative lodges.’

William Oughtred. Line engraving by [F. S.], 1667, after W. Hollar..

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection – Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

This new circle of friends revolved around William Oughtred, the mathematician, alchemist, astrologer and inventor of the slide rule, who had tutored him at Oxford.

Among Oughtred’s friends were Seth Ward, Jonas Moore, Thomas Henshaw, Christopher Wren, William Lilly, George Wharton and Thomas Wharton. And within a year, Ashmole became a regular visitor to Gresham College, the institution which was so important as a meeting place for the founder members of the Royal Society.

By 17 June 1652, he was well enough established to be visited by two supporters of Oliver Cromwell, John Wilkins and Christopher Wren.

Wilkins was a successful Parliamentarian academic, warden of Wadham College and was courting Robina, the sister of the Oliver Cromwell.

Ashmole wrote in his diary:

‘11H.A.M: Doctor Wilkins & Mr: Wren came to visit me at Blackfriers. this was the first tyme I saw the Doctor.’

Wren had just been appointed a fellow of All Souls, Cambridge. Both Ashmole’s visitors enjoyed the patronage of the Cromwell family.

His new Masonic connections seem to have encouraged these two successful academics to visit a disgraced Royalist ex-officer, living illegally in London.

Whatever the reason, Ashmole used his contacts to re-establish his livelihood in London and was then able return to the Mainwaring family to persuade his late wife’s cousin, three times widowed, Lady Mary Mainwaring to take him as her fourth husband.

When they married in 1649, she was 52 he was 32. The marriage provided Ashmole with the income from Mary’s first husband’s estates and left him wealthy enough to pursue his interests, including botany, alchemy and occult philosophy, without the need to earn a living.

The bride’s family opposed the marriage, but she went ahead. The match did not prove harmonious, she filed suit for separation and alimony some 7 years after the betrothal, however her action was dismissed by the courts in 1657.

Ashmole was too fond of her money to let her go. Instead, he arranged for his friend George Wharton to be released from prison (for writing libellous satires of Parliament) to manage Mary’s estates on his behalf.

John Tradescant I. Etching by W. Hollar, 1656, after E. (?) de Critz..

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection – Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

In 1656, he used Mary’s money to buy his way into John Tradescant’s affections by funding a catalogue of Tradescant’s Collection of exotic plants, mineral specimens and curiosities from around the world.

Tradescant left the collection to Ashmole after his death, against his family’s wishes, and Ashmole later it used to establish the Ashmolean Museum.

His determined aggressiveness in obtaining the Tradescant collection for himself, led to Hester, Tradescant’s widow to drown herself in her own garden pond.

These incidents lead me to think that Ashmole was an ambitious, ingratiating social climber who stole a hero’s legacy for his own glorification.

He certainly had intellectual ability, but his actions do not suggest he had any charitable or benevolent tendencies. He took to writing worthy books as soon as Mary’s money was firmly under his control.

He must have neglected Mary while writing his first four books, as just as he published Musaeum Tradescantianum as the first step of his plan to acquire the Tradescant Collection, Mary sued him for divorce.

To celebrate her failure to escape his clutches and resume control of her money, he published The Way to Bliss, which does seem to have certain irony about it.

Hester Tradescant. Line engraving, 1798.

IMAGE LINKED: welcome collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

On 3 January 1661, Ashmole was invited to become a member of the newly formed Royal Society.

Its library holds some neat hand-written entries that show somebody was keen to get him into the group.

He was proposed at the second meeting. Then, within a fortnight, he was put forward again.

Why was it so important to bring him into the new Society for Promoting Philosophical Knowledge by Experiments that he was proposed on two separate occasions? It wasn’t because he was a great scientist, as he contributed little to the work of the Society.

His only pretension to science was the study of astrology. But he did pay his dues regularly and was keen to curry favour with the king. Ashmole, as the beneficiary of Mary’s considerable fortune, could be trusted to buy his way into favour, and the Society needed money.

His diary entry dated 3 January 1661, says:

‘This afternoone I was voted into the Royall Society at Gresham College.’

Ashmole added his signature to the extended list of 114, who had been proposed at the meeting held on 5 December 1660.

His diary records on 9 January 1661:

‘This afternoon I went to take my place among the Royall Society at Gresham College.’

The record of the Royal Society of London for the promotion of natural knowledge

IMAGE LINKED: welcome collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

He did not attend many meetings at Gresham, though by this time his support for the king’s new Royal Society had already got him the plum job of Windsor Herald.

Perhaps he was too busy preparing for the coronation, which was now part of his official heraldic duties.

But the Society’s records show that he paid his subscriptions promptly even when he didn’t take an active part in the scientific work.

Even though Ashmole was a poor attender, he was one of the first fellows to sign a binding bond of payment to guarantee the Society’s income.

The Society’s minutes for 22 October 1673, listed fifty-seven persons ‘that may be looked upon as good paymasters’, and Ashmole’s name tops this list.

On 7 March 1676, as an example of his largesse with Mary’s money, he gave an extra £5 above his normal subscription, to set up a fund to provide the Society with its own building.

I suspect that Ashmole supported the Society to win the favour of the king, who was its patron. [If you are interested in learning about his role, and that of other Freemason’s of the time, in setting up the Royal Society then I suggest reading my book, Freemasonry and the Birth of Modern Science where there is a full chapter on Ashmole’s role.]

Frontispiece of Ashmole’s ‘The Way to Bliss’, 1658

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Mary Ashmole, nee Lady Mainwaring, died in 1668, aged 71. As Elias inherited all her assets he wasn’t too upset, and quickly set about looking for a new wife.

This time he wasn’t after another rich widow, he had his inherited wealth and had already tricked John Tradescant the Younger into bequeathing the Tradescant Collection to him in 1662.

This was despite the legal opposition of Tradescant’s second wife Hester, who soon after losing the lawsuit committed suicide.

For the first time Elias married a younger woman. Perhaps he was hoping for an heir to pass his riches to.

He chose Elizabeth Dugdale who married him six months after Mary’s death.

She was 36 years old and Ashmole was 51. I believe his motive for marrying her was to gain esteem, as she was the daughter of William Dugdale, who was Norroy King of Arms and in line to be appointed the next Garter King of Arms.

Ashmole was then Windsor Herald and was writing a book on the Order of Garter, which he hoped would win him greater favour with Charles II.

His ambition, shared with his diary, was to become official historiographer of the Order of Garter.

Sir William Dugdale, as his father-in-law, was potentially a useful source for the material Ashmole would need.

The book was published as The Institutions, Laws, and Ceremonies of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, in 1672, and dedicated to Charles II.

His father-in-law was duly appointed Garter King of Arms in 1677.

Despite his age, Elias took to the prospect of fatherhood with great enthusiasm as Elizabeth fell pregnant three times over the next four years.

Sadly, all his efforts ended in stillbirths or miscarriages. In 1677, after Elizabeth had gone through the menopause, Elias accepted that he would die childless.

In 1677, having no heir, he endowed the Ashmolean Museum to ensure his memory would live on, as it has.

The following year, 1678, he stood for parliament in Lichfield Borough but was not elected.

He tried again in 1685 but ending up selling his votes (it was a rotten borough) to King James II’s preferred candidate.

He never lost his talent of using his connections to boost his own reputation, as we can see in his diary entry of 11 March 1682. Just as he was about to publish a biography of the famous Christian Astrologer and Freemason, William Lilly, Bro Ashmole records in his diary:

‘I went, & about Noone were admitted into the Fellowship of Free Masons. Sir William Wilson: Knight, Capt. Rich: Borthwick, Mr Will: Woodman, Mr Wm Grey, Mr Samuel Taylor & Mr William Wise. I was the Senior Fellow among them (it being 35 years since I was admitted) … Wee all dynerd at the halfe Moone Tavern in Cheapside, at a Noble dinner prepared at the charge of the Newly Accepted Masons.’

I wonder if he mentioned his intention to publish a book which linked his name to William Lilly at the festive board? (No signed copies have been found to test this hypothesis.)

He died on 18 May 1692. Elizabeth outlived him, and two years after his death on 15 March 1694, she married John Reynolds. She died in 1701, at the age of 81.

Richard Garnett’s entry in the 1891 Dictionary of National Biography sums up my view of Ashmole quite clearly. He says, ‘acquisitiveness was his master passion’.

That is not to say that Ashmole lacked intellectual ability, he wrote many learned books, which I have listed in date order below.

But they were all written after he took control of Mary’s money and could afford to spend his time pursuing his own interests.

(1650) Fasciculus Chemicus: Using the pen name James Hasolle.

(1652) Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum.

(1652) The Brevity of Natural Philosophy [in Verse]

(1656) Musaeum Tradescantianum.

(1658) The Way to Bliss. [In Three Volumes]

(1660) The Glorious Appearance of Charles II up on the Horizon of London. [Verses]

(1662) The Entire Ceremonies of the Coronation of HM King Charles II

(1666) The Visitation of Berkshire 1664-5

(1672) The Institutions, Laws, and Ceremonies of the Most Noble Order of the Garter

(1682) A History of the Life and Times of William Lilly

Theatrum chemicum Britannicum. Containing severall poeticall pieces of our famous English philosophers, who have written the Hermetique mysteries in their owne ancient language / Faithfully collected into one volume, with annotations thereon, by Elias Ashmole, esq. Qui est Mercuriophilus anglicus. The first part..

IMAGE LINKED: welcome collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Certainly, Elias Ashmole was an early English Freemason, but he was also an opportunist who always had an eye towards his own best interests.

Finding himself on the losing side, at the end of the Civil War, he was prepared to try anything to improve his position.

Unable to find a wealthy widow to support him, he joined Freemasonry with a view to using it to open doors for him in London. As soon as he was initiated, he set off to London and those doors did open into the upper reaches of the Parliamentary society.

Now earning a living, he was able to seduce Lady Mary Mainwaring and gain control of her fortune. As my good friend Yasha Beresiner said of him:

‘Ashmole was an extraordinarily accomplished man. By 1648, he had extended his studies in Astrology and Anatomy to Botany and Alchemy. This last subject was to occupy him considerably and he wrote several books on the subject, the first in 1650. He was undoubtedly fascinated with esoteric and hermetic studies. He often consulted oracles.’

This is perfectly true, but his diary reveals he also exploited elderly widows and ageing collectors of scientific oddities to get control of financial, scientific, and other useful information which he could use to his own advantage.

He got his first taste for money by marrying an elderly spinster of modest means then consolidated his fortunes by marrying an even older thrice-widowed woman of substance, to use her money for his own aims.

Finally, realising he would leave no heirs he married the younger daughter of an influential friend who had access to material he needed to write his History of the Order of Garter.

The world certainly benefited from his failure to father a child, as to secure the memory of his own importance he endowed Oxford University with his ill-gotten gains by founding the Ashmolean Museum.

In the end his talent for acquisitiveness was turned to the public good.

But does that make him a Masonic Hero? A shining example of an early practitioner of Brotherly Love, Relief and Truth? I don’t think so.

The facts show him to be untrustworthy with women, an exploiter of elderly collectors and someone who would use social and Masonic contacts before moving on and ignoring them as better opportunities came along.

So, Masonic Hero or Scheming Chancer? I’ve made up my mind, but I’ve given you the facts to decide for yourself.

Postscript

During lockdown I did two video interviews with Antonio Russo for the Lewis Masonic YouTube Channel

In the second part I mentioned my views on Elias Ashmole, that I have outlined above and which I had published in a podcast called ‘Elias Ashmole Warts and All, in his own words’.

A few weeks later Antonio mentioned he has been speaking to Yasha Beresiner who thought I was being a little hard on Bro Elias.

Antonio suggested that Yasha and I debate the question ‘Is Elias Ashmole a Masonic Hero or a Scheming Chancer?’

That debate was to be recorded and then shown to an independent jury of masonic scholars to decide who had made the best case.

I proposed the motion ‘That Elias Ashmole is a Scheming Chancer’, and Yasha countered with that motion that ‘Elias Ashmole is Masonic Hero’. Antonio chaired the debate.

The video was shown to the jury, and they recorded their comments and verdict.

The two videos will be published on the Lewis Masonic YouTube channel.

Perhaps you might care to watch them and see if you agree with the verdict.

Zoom Video – approx 60 mins

In this video the Jury make a judgement on this debate.

Article by: Robert Lomas

Robert Lomas has a BSc (First Class Honours) in Electronics and a PhD in the Quantum Physics of Solid State Devices.

He became a Freemason in 1987. Robert has a long-time interest in Masonic Education and for the last 24 years has been a regular lecturer on Masonic topics at lodges throughout the UK as well as abroad.

He co-authored the international best seller 'The Hiram Key'. Robert’s writings have been translated into 54 different languages.

Recent Articles: by Robert Lomas

Meet The Author

Editor Philippa Lee interviews well-known Masonic author Dr Robert Lomas

more....

Book Review - The Masonic Tutor's Handbook 2

A review of The Masonic Tutor's Handbooks: Vol 2 - Freemasonry - After Covid 19 by Robert Lomas

more....

Book Review - The Masonic Tutor's Handbook 3

Becoming a Craftsman -The Masonic Tutor's Handbooks: Volume 3 - The relationship between a Fellowcraft and their Master is how the traditional wisdom of our Craft is passed on.

more....

Elias Ashmole: Masonic Hero or Scheming Chancer?

The debate is on! Two eminent Masonic scholars go head to head: Yasha Beresiner proposes that Elias Ashmole was 'a Masonic hero', whereas Robert Lomas posits that Ashmole was a 'scheming chancer'.

more....

Recent Articles: in people series

Celebrate the extraordinary legacy of The Marquis de La Fayette with C.F. William Maurer's insightful exploration of Lafayette's 1824-25 tour of America. Discover how this revered leader and Freemason was honored by a young nation eager to showcase its growth and pay tribute to a hero of the American Revolution. |

Albert Mackey and the Civil War In the midst of the Civil War's darkness, Dr. Albert G. Mackey, a devoted Freemason, shone a light of brotherhood and peace. Despite the nation's divide, Mackey tirelessly advocated for unity and compassion, embodying Freemasonry's highest ideals—fraternal love and mutual aid. His actions remind us that even in dire times, humanity's best qualities can prevail. |

Discover the enduring bond of brotherhood at Lodge Dumfries Kilwinning No. 53, Scotland's oldest Masonic lodge with rich historical roots and cultural ties to poet Robert Burns. Experience rituals steeped in tradition, fostering unity and shared values, proving Freemasonry's timeless relevance in bridging cultural and global divides. Embrace the spirit of universal fraternity. |

Discover the profound connections between John Ruskin's architectural philosophies and Freemasonry's symbolic principles. Delve into a world where craftsmanship, morality, and beauty intertwine, revealing timeless values that transcend individual ideas. Explore how these parallels enrich our understanding of cultural history, urging us to appreciate the deep impacts of architectural symbolism on society’s moral fabric. |

Discover the incredible tale of the Taxil Hoax: a stunning testament to human gullibility. Unmasked by its mastermind, Leo Taxil, this elaborate scheme shook the world by fusing Freemasonry with diabolical plots, all crafted from lies. Dive into a story of deception that highlights our capacity for belief and the astonishing extents of our credulity. A reminder – question everything. |

Dive into the extraordinary legacy of Alexander Von Humboldt, an intrepid explorer who defied boundaries to quench his insatiable thirst for knowledge. Embarking on a perilous five-year journey, Humboldt unveiled the Earth’s secrets, laying the foundation for modern conservationism. Discover his timeless impact on science and the spirit of exploration. |

Voltaire - Freethinker and Freemason Discover the intriguing connection between the Enlightenment genius, Voltaire, and his association with Freemasonry in his final days. Unveil how his initiation into this secretive organization aligned with his lifelong pursuit of knowledge, civil liberties, and societal progress. Explore a captivating facet of Voltaire's remarkable legacy. |

Robert Burns; But not as we know him A controversial subject but one that needs addressing. Robert Burns has not only been tarred with the presentism brush of being associated with slavery, but more scaldingly accused of being a rapist - a 'Weinstein sex pest' of his age. |

Richard Parsons, 1st Earl of Rosse Discover the captivating story of Richard Parsons, 1st Earl of Rosse, the First Grand Master of Grand Lodge of Ireland, as we explore his rise to nobility, scandalous affiliations, and lasting legacy in 18th-century Irish history. Uncover the hidden secrets of this influential figure and delve into his intriguing associations and personal life. |

James Gibbs St. Mary-Le-Strand Church Ricky Pound examines the mysterious carvings etched into the wall at St Mary-Le-Strand Church in the heart of London - are they just stonemasons' marks or a Freemason’s legacy? |

Freemasonry and the Royal Family In the annals of British history, Freemasonry occupies a distinctive place. This centuries-old society, cloaked in symbolism and known for its masonic rituals, has intertwined with the British Royal Family in fascinating ways. The relationship between Freemasonry and the Royal Family is as complex as it is enduring, a melding of tradition, power, and mystery that continues to captivate the public imagination. |

A Man Of High Ideals: Kenneth Wilson MA A biography of Kenneth Wilson, his life at Wellington College, and freemasonry in New Zealand by W. Bro Geoff Davies PGD and Rhys Davies |

In 1786, intending to emigrate to Jamaica, Robert Burns wrote one of his finest poetical pieces – a poignant Farewell to Freemasonry that he wrote for his Brethren of St. James's Lodge, Tarbolton. |

Alex Lishanin explores Mumbai and discovers the story of Lodge Rising Star of Western India and Manockjee Cursetjee – the first Indian to enter the Masonic Brotherhood of India. |

Aleister Crowley - a very irregular Freemason Aleister Crowley, although made a Freemason in France, held a desire to be recognised as a 'regular' Freemason within the jurisdiction of UGLE – a goal that was never achieved. |

Sir Joseph Banks – The botanical Freemason Banks was also the first Freemason to set foot in Australia, who was at the time, on a combined Royal Navy & Royal Society scientific expedition to the South Pacific Ocean on HMS Endeavour led by Captain James Cook. |

Making a Mason in Prison: the John Wilkes’ exception? |

"To be a good man and true" is the first great lesson a man should learn, and over 40 years of being just that in example, Dr Buck won the right to lay down the precept. |

Elias Ashmole: Masonic Hero or Scheming Chancer? The debate is on! Two eminent Masonic scholars go head to head: Yasha Beresiner proposes that Elias Ashmole was 'a Masonic hero', whereas Robert Lomas posits that Ashmole was a 'scheming chancer'. |

Sir Arthur Sullivan - A Masonic Composer We are all familiar with the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan, but did you know Sullivan was a Freemason, lets find out more…. |

The Much-Maligned Dr John Misaubin The reputation of the Huguenot Freemason, has been buffeted by waves of criticism for the best part of three hundred years. |

Was William Morgan really murdered by Masons in 1826? And what was the lie Masonic author Rob Morris told? Find out more in the intriguing story of 'The Morgan Affair'. |

Lived Respected - Died Regretted Lived Respected - Died Regretted: a tribute to HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh |

Who was Moses Jacob Ezekiel, a Freemason, American Civil War Soldier, renowned sculptor ? |

A Masonic author and Provincial Grand Master of Forfarshire in Scotland |

Who was Philip, Duke of Wharton and was he Freemasonry’s Loose Cannon Ball ? |

Richard Carlile - The Manual of Freemasonry Will the real author behind The Manual of Freemasonry please stand up! |

Nicholas Hawksmoor – the ‘Devil’s Architect’ Nicholas Hawksmoor was one of the 18th century’s most prolific architects |

By Bro. Anthony Oneal Haye (1838-1877), Past Poet Laureate, Lodge Canongate Kilwinning No. 2, Edinburgh. |

The Curious Case of the Chevalier d’Éon A cross-dressing author, diplomat, soldier and spy, the Le Chevalier D'Éon, a man who passed as a woman, became a legend in his own lifetime. |

Mozart Freemasonry and The Magic Flute. Rev'd Dr Peter Mullen provides a historical view on the interesting topics |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device