“For what does Masonry exist? What is the end and purpose of the order?”

Roscoe Pound‘s ‘Lectures on the Philosophy of Freemasonry’ (1915), is probably one of the most concise and worthy explanations as to the subject.

Written in 1915, his words are as relevant today, as they were over one hundred years ago and we will extensively use his text in this article.

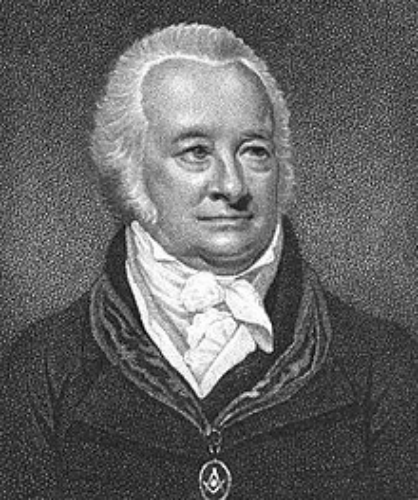

Roscoe Pound, c. 1916

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

In his work he asked three fundamental questions:

1. What is the nature and purpose of Masonry as an institution? For what does it exist? What does it seek to do? Of course for the philosopher this in- volves also and chiefly the questions, what ought Masonry to be? For what ought it to exist ? What ought it to seek as its end?

2. What is — and this involves what should be — the relation of Masonry to other human institutions, especially to those directed toward similar ends ? What is its place in a rational scheme of human activities?

3. What are the fundamental principles by which Masonry is governed in attaining the end it seeks? This again, to the philosopher, involves the question what those principles ought to be.

First things first – how did Pound describe ‘Masonic philosophy’?

“It is enough to say at the outset that in the sense in which philosophers of Masonry have used the term, philosophy is the science of fundamentals.

Possibly it would be more correct to think of the philosophy of Masonry as organized Masonic knowledge — as a system of Masonic knowledge.

But there has come to be a well-defined branch of Masonic learning which has to do with certain fundamental questions; and these fundamental questions may be called the problems of Masonic philosophy, since that branch of Masonic learning which treats of them has been called commonly the philosophy of Masonry…

Four eminent Masonic scholars have essayed to answer these questions and in so doing have given us four systems of Masonic philosophy, namely; William Preston, Karl Christian Friedrich Krause, George Oliver and Albert Pike.

Of these four systems of Masonic philosophy, two, if I may put it so, are intellectual systems. They appeal to and are based upon reason only. These two are the system of Preston and that of Krause.

The other two are, if I may put it that way, spiritual systems. They do not flow from the rationalism of the eighteenth century but spring instead from a reaction toward the mystic ideas of the hermetic philosophers in the seventeenth century.”

William Preston, from the 1812 edition of ‘Illustrations of Masonry’

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The first ‘system’ or school of Masonic philosophy was that proposed by Masonic scholar William Preston: the keyword to his system is ‘Knowledge’.

So, who was William Preston, the first advocate of Masonic Knowledge?

Preston (1742-1818) was a Scottish author, editor and lecturer. Preston joined Freemasonry whilst working in London for the King’s Printer William Strahan.

A group of Scots Masons living in the capital who had decided to form Lodge No. 111 which was under the jurisdiction of the Ancient Grand Lodge, (known as the ‘Ancients/Antients’).

However, it wasn’t long before Preston and some of his brethren became unhappy with the status of this ‘new’ Grand Lodge and changed allegiance to the Premier Grand Lodge of England, known as the ‘Moderns’.

Subsequently, Lodge No. 111 (of the Ancients) became Caledonian Lodge no 325 (of the Moderns).

[Note: Antient/ancient and Modern referred to the ritual used by the respective Constitutions, not to the age of the Grand Lodges.]

In 1777, Preston and several members of the Lodge of Antiquity returned from church wearing their Masonic regalia.

As ‘processions’ in Masonic regalia were proscribed, he was expelled from Grand Lodge.

Several years later he was allowed to return, and he immersed himself in the study of Masonic history and philosophy.

He founded the Order (or Grand Chapter) of Harodim, which was the vehicle for his passion for Masonic knowledge, he then wrote his seminal work Illustrations of Freemasonry.

The Prestonian Lecture is an annual lectureship given under the authority of the United Grand Lodge of England, the legacy of William Preston’s work as a Masonic educator.

‘During his lifetime William Preston developed an elaborate system of masonic instruction which was practised in association with the Lodge of Antiquity of which he was at one time Master.

At his death in 1818, Preston bequeathed to Grand Lodge the sum of £300 for the perpetuation of his system of instruction…

Lectures in accordance with this system were delivered from 1820 until 1862, when the Lectureship was permitted to lapse.

In 1924 the Prestonian Lectureship was revived with a modification to the original Scheme, the lecturer now submitting a Masonic subject of his own selection, and with the exception of the war years, 1940-1946, regular appointments have been made annually since 1924 to the present day.’

– Source: Text from the Grand Lodge of England Masonic Year Book.

William Preston was a product of the 18th century, and in Pound’s words we should understand that:

Three striking characteristics of the first three quarters of the eighteenth century in England are of importance for an understanding of Preston’s philosophy of Masonry:

(1) It was a period of mental quiescence;

(2) both in England and elsewhere it was a period of formal over-refinement;

(3) it was the so- called age of reason, when the intellect was taken to be self-sufficient and men were sure that knowledge was a panacea…

We must remember that Preston, who worked twelve hours a day setting type or reading proof, would look on this very differently from the Mason of today.

What are commonplaces of science now were by no means general property then…to Preston, first and above all else the Masonic order existed to propagate and diffuse knowledge.

To this end, therefore, he seized upon the opportunity afforded by the lectures and sought by means of them to develop in an intelligent whole all the knowledge of his day.

So, what would have been Preston’s answers to those three fundamental questions?

From Pound’s ‘Lectures’:

1. For what does Masonry exist? What is the end and purpose of the order?

To diffuse light, that is, to spread knowledge among men. That above all things Masonry exists to promote knowledge; the Mason ought first of all to cultivate his mind, he ought to study the liberal arts and sciences; he ought to become a learned man.

2. What is the relation of Masonry to other human activities?

Preston does not answer this question directly anywhere in his writings. But we may gather that he would have said something like this:

The state seeks to make men better and happier by preserving order. The church seeks this end by cultivating the moral person and by holding in the background supernatural sanctions.

Masonry endeavors to make men better and happier by teaching them and by diffusing knowledge among them.

3. How does Masonry seek to achieve its purposes? What are the principles by which it is governed in attaining its end?

Preston answers that both by symbols and by lectures the Mason is (first) admonished to study and to acquire learning and (second) actually taught a complete system of organized knowledge.

We have his own words for both of these ideas. As to the first, in his system both lectures and charges reiterate it. For example:

The study of the liberal arts, that valuable branch of education which tends so effectually to polish and adorn the mind is earnestly recommended to your consideration…

Grammar teaches the proper arrangement of words according to the idiom or dialect of any particular people, and that excellency of pronunciation which enables us to speak or write a language with accuracy, agreeably to reason and correct usage.

Rhetoric teaches us to speak copiously and fluently on any subject, not merely with propriety alone, but with all the advantages of force and elegance, wisely contriving to captivate the hearer by strength of argument and beauty of expression, whether it be to entreat and exhort, to admonish or applaud.

As to the second proposition, one example will suffice:

Tools and implements of architecture are selected by the fraternity to imprint on the memory wise and serious truths.

In other words the purpose even of the symbols is to teach wise and serious truths. The word ‘serious’ here is significant.

It is palpably a hit at those of his brethren who were inclined to be mystics and to dabble in what Preston regarded as the empty jargon of the hermetic philosophers.

Finally, to show his estimate of what he was doing and hence what, in his view, Masonic lectures should be, he says himself of his Fellowcraft lecture: This lecture contains a regular system of science [note that science then meant knowledge] demonstrated on the clearest principles and established on the firmest foundation.

What follows is the summing up of Preston’s views by Pound:

One need not say that we cannot accept the Prestonian philosophy of Masonry as sufficient for the Masons of today.

Much less can we accept the details or even the general framework of his ambitious scheme to expound all knowledge and set forth a complete outline of a liberal education in three lectures.

We need not wonder that Masonic philosophy has made so little headway in Anglo-American Masonry when we reflect that this is what we have been brought up on and that it is all that most Masons ever hear of.

It comes with an official sanction that seems to preclude inquiry, and we forget the purpose of it in its obsolete details.

But I suspect we do Preston a great injustice in thus preserving the literal terms of the lectures at the expense of their fundamental idea.

In his day they did teach — today they do not. Suppose today a man of Preston’s tireless diligence attempted a new set of lectures which should unify knowledge and present its essentials so that the ordinary man could comprehend them.

To use Preston’s words, suppose lectures were written, as a result of seven years of labor, and the co-operation of a society of critics, which set forth a regular system of modem knowledge demonstrated on the clearest principles and established on the firmest foundation.

Suppose, if you will, that this were confined simply to knowledge of Masonry. Would not Preston’s real idea (in an age of public schools) be more truly carried out than by our present lip service, and would not his central notion of the lodge as a center of light vindicate itself by its results?

Let me give two examples.

In Preston’s day, there was a general need, from which Preston had suffered, of popular education — of providing the means whereby the common man could acquire knowledge in general.

Today there is no less general need of a special kind of knowledge.

Society is divided sharply into classes that understand each other none too well and hence are getting wholly out of sympathy.

What nobler Masonic lecture could there be than one which took up the fundamentals of social science and undertook to spread a sound knowledge of it among all Masons?

Suppose such a lecture was composed as Preston’s lectures were, was tried on by delivery in lodge after lodge, as his were, and after criticism and recasting as a result of years of labor, was taught to all our masters.

Would not our lodges diffuse a real light in the community and take a great step forward in their work of making for human perfection?

Again, in spite of what is happening for the moment upon the Continent, this is an era of universality and internationality.

The thinking world is tending strongly to insist upon breaking over narrow local boundaries and upon looking at things from a world-wide point of view.

Art, science, economics, labor and fraternal organizations, and even sport are tending to become international.

The growing frequency of international congresses and conferences upon all manner of subjects emphasizes this breaking of local political bonds.

The sociological movement, the world over, is causing men to take a broader and more humane view, is causing them to think more of society and hence more of the world-society, is causing them to focus their vision less upon the individual, and hence less upon the individual locality.

In this world-wide movement toward universality Masons ought to take the lead. But how much does the busy Mason know, much less think, of the movement for internationality or even the pacificist movement which has been going forward all about him?

Yet every Mason ought to know these things and ought to take them to heart.

Every lodge ought to be a center of light from which men go forth filled with new ideas of social justice, cosmopolitan justice and internationality.

Preston of course was wrong — knowledge is not the sole end of Masonry.

But in another way Preston was right. Knowledge is one end — at least one proximate end — and it is not the least of those by which human perfection shall be attained.

Preston’s mistakes were the mistakes of his century — the mistake of faith in the finality of what was known to that era, and the mistake of regarding correct formal presentation as the one sound method of instruction.

But what shall be said of the greater mistake we make today, when we go on reciting his lectures — shorn and abridged till they mean nothing to the hearer — and gravely presenting them as a system of Masonic knowledge?

Bear in mind, he thought of them as presenting a general scheme of knowledge, not as a system of purely Masonic information.

If we were governed by his spirit, understood the root idea of his philosophy and had but half his zeal and diligence, surely we could make our lectures and through them our lodges a real force in society.

Here indeed, we should encounter the precisions and formalists of whom lodges have always been full, and should be charged with innovation.

But Preston was called an innovator. And he was one in the sense that he put new lectures in the place of the old reading of the Gothic constitutions.

Preston encountered the same precisions and the same formalists and wrote our lectures in their despite.

I hate to think that all initiative is gone from our order and that no new Preston will arise to take up his conception of Knowledge as an end of the fraternity and present to the Masons of today the knowledge which they ought to possess.

No doubt that some years after these words were written, Roscoe Pound began to see new ‘Prestons’ rise up and present their knowledge and research to the Masons of today via the Prestonian Lectureship.

However, these lectures are invariably academic in tone and rarely of interest to non-academic Freemasons – that still leaves a vacuum for those who seek but perhaps never find the ‘end and purpose of the Order’.

Text Source: Lectures on the Philosophy of Freemasonry by Roscoe Pound, 1915.

Article by: Philippa Lee. Editor

Philippa Lee (writes as Philippa Faulks) is the author of eight books, an editor and researcher.

Philippa was initiated into the Honourable Fraternity of Ancient Freemasons (HFAF) in 2014.

Her specialism is ancient Egypt, Freemasonry, comparative religions and social history. She has several books in progress on the subject of ancient and modern Egypt. Selection of Books Online at Amazon

Lectures on the Philosophy of Freemasonry

By:Roscoe Pound

This work has been selected by scholars as being culturally important, and is part of the knowledge base of civilization as we know it. This work was reproduced from the original artifact, and remains as true to the original work as possible.

Therefore, you will see the original copyright references, library stamps (as most of these works have been housed in our most important libraries around the world), and other notations in the work.

This work is in the public domain in the United States of America, and possibly other nations. Within the United States, you may freely copy and distribute this work, as no entity (individual or corporate) has a copyright on the body of the work.

As a reproduction of a historical artifact, this work may contain missing or blurred pages, poor pictures, errant marks, etc.

Scholars believe, and we concur, that this work is important enough to be preserved, reproduced, and made generally available to the public.

We appreciate your support of the preservation process, and thank you for being an important part of keeping this knowledge alive and relevant.

Illustrations of Masonry.

By: William Preston (Author)

This work has been selected by scholars as being culturally important, and is part of the knowledge base of civilization as we know it.

This work was reproduced from the original artifact, and remains as true to the original work as possible. Therefore, you will see the original copyright references, library stamps (as most of these works have been housed in our most important libraries around the world), and other notations in the work.

This work is in the public domain in the United States of America, and possibly other nations. Within the United States, you may freely copy and distribute this work, as no entity (individual or corporate) has a copyright on the body of the work.

As a reproduction of a historical artifact, this work may contain missing or blurred pages, poor pictures, errant marks, etc. Scholars believe, and we concur, that this work is important enough to be preserved, reproduced, and made generally available to the public.

We appreciate your support of the preservation process, and thank you for being an important part of keeping this knowledge alive and relevant.

Recent Articles: Eight Schools of Freemasonry

8 Schools of Freemasonry - Romantic P8 We end this series with the 'Romantic School'. Not a flowery tribute but one that explores the various 'romantic' theories as to the origins of Freemasonry, such as the Biblical aspects, the stone masons guilds, the Knights Templar. |

8 Schools of Freemasonry - Esoteric P7 The Esoteric School – Arthur Edward Waite viewed Freemasonry as a form of mystical teaching. He taught that enlightenment was achieved through the perfection of the self via the study of arcane knowledge and practice of occult rites. |

8 Schools of Freemasonry - Historic P6 A dedication to fact-based historical writings as opposed to the 'traditional' or 'romantic' history, led a group of prominent Freemasons to form what would become known as the 'Authentic School' of Freemasonry. |

8 Schools of Freemasonry - Philosophy P5 To finish with Roscoe Pound's invaluable work on the Philosophies of Freemasonry, we look at his final summing up: A Twentieth-Century Masonic Philosophy: The Relation of Masonry to Civilisation. |

8 Schools of Freemasonry - Philosophy P4 The Philosophy of Masonry – Metaphysics and Symbolism. Following on from Part 3 of The Eight Schools of Freemasonry, we move on to Albert Pike, whose Masonic spiritual philosophy was concerned with Symbolism. |

8 Schools of Freemasonry - Philosophy P3 The Philosophy of Masonry – Religion. Following on from Part 2 of The Eight Schools of Freemasonry, we explore the Religious School of the Rev. George Oliver. |

8 Schools of Freemasonry - Philosophy P2 Following on from Part 1 of The Eight Schools of Freemasonry which discussed William Preston's School of Masonic Education, we explore the Philosophical School of Karl Christian Friedrich Krause. |

8 Schools of Freemasonry - Philosophy P1 For what does Masonry exist? What is the end and purpose of the order? - Roscoe Pound's Lectures on the Philosophy of Freemasonry (1915), is probably one of the most concise and worthy explanation as to the subject. |

8 Schools of Freemasonry - Introduction Follow this series as examine the 'Eight Schools of Freemasonry' that have developed over the centuries since its founding in 1717. This month we outline the series and the Masonic Conception of Education. |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device