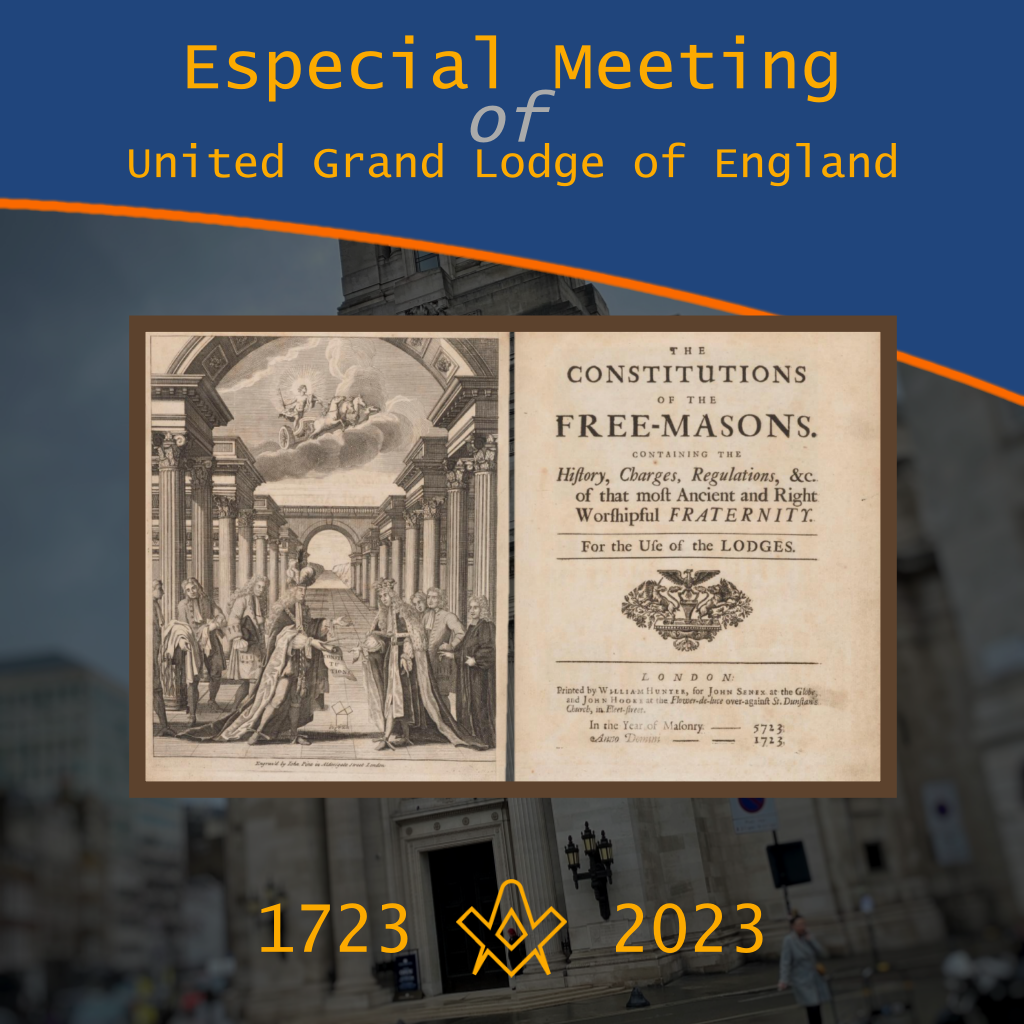

An Especial meeting was held at Freemasons Hall by United Grand Lodge of England to commemorate the tercentenary of the 1723 Constitutions.

Though the Freemasons assembled were all in dress regalia, the lodge did not open. There were many guests, representing Grand Lodges from around the world, including the two Grand Masters of the female-only members lodges of England, the (OWF) Order of Women’s Freemasonry, and (HFAF) Honourable Fraternity of Ancient Freemasons.

The gathering was presented in three parts:

Dr Ric Berman’s presentation of the 1723 constitutions

A short film dramatizing the writing of the book

Akram Elias, Prestonian Lecturer for 2023 and former GM of the Grand Lodge of Washington DC, prsented the 2023 Prestonian Lecture.

The year 2023 marks the tercentenary of the publication in London of the Constitutions of the Freemasons, based on Enlightenment principles that provide the philosophical foundations of modern Freemasonry.

Why are the 1723 Constitutions important?

Many Masonic histories have been concerned with ‘when’ and ‘what’. We also explore ‘why?’

The 1723 Constitutions championed Enlightenment ideas:

• Religious tolerance, which was radical in a world characterised by religious conflict

• Constitutional government–‘the supreme legislature’, not the absolutism of a divinely appointed monarch

• Meritocracy at a time when birth and wealth determined success

• High standards of interpersonal civility

• Education and science – a world interpreted through rational observation rather than religious diktat

• Personal and societal self-improvement.

The 1723 Constitutions also provided a rulebook for Freemasonry – the ‘Regulations’ – and a structure emulated by many other secular clubs and societies in Britain and around the world.

Masonic practices included:

• The election of officers subject to democratic accountability, with one member wielding one vote

• Majority rule

• Orations by elected officials

• National federal governance

• Written constitutions and bylaws.

Inventing the future

Presented by Ric Berman

Highlights of his presentation:

• Religious tolerance, something wholly radical in a world characterised by religious conflict;

• meritocracy and aspiration at a time when birth and wealth determined success;

• high standards of interpersonal civility;

• scientific and artistic education; and societal and personal self-improvement.

Why are the members of United Grand Lodge of England celebrating the 300 year anniversary of the 1723 Book of Constitutions?

Dr Ric Berman, editor of the micro website 1723 constitutions.com helps shed some light on this year long celebration.

Freemasons, and the general public, would benefit greatly from knowing just how radical the 1723 constitutions were and the kind of change they wrought.

Moreover, it is important to grasp their historical background, origins, and the ripple effects they eventually had.

Before the 1723 constitutions were published, Freemasonry was, at best, a relatively unknown organisation, expanding from the operative lodges in Scotland, to social gatherings in England. This was the case both in the 17th century and earlier years, but also at the beginning of the 18th century.

But the constitutions of 1723 changed Freemasonry by establishing enlightenment philosophical principles, and this was a huge break from the old charges that had governed mediaeval Freemasonry and stonemasons lodges before then.

The most significant shift was the emphasis placed on religious tolerance. We must not discount this any longer.

Looking at Europe in the early 18th century, or even from the time of the Reformation in the 1540s until the early 18th century, you will see countries torn apart by religious strife, with hundreds of thousands of people killed.

France in particular, but also Spain and Portugal, and Italy, continued to display this phenomenon well into the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

The war between Protestants and Catholics has claimed the lives of tens of thousands of people once again.

So, openness to other faiths was revolutionary.

In a world where religion is a source of conflict, it was revolutionary. Freemasons, according to the second theory, would be obligated to abide by the principles of constitutional government, which include a monarchy, an elected parliament, and an independent judiciary.

If we return to Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, we see countries ruled by absolute monarchies.

Once again, we see the influence of Catholicism and the central notion that the monarch (usually the king) is a divinely appointed Monique endowed with absolute power.

Keep in mind that this was the case up until the 1680s in England; it wasn’t until 1689 that James II was deposed and William and Mary were crowned, and the first thing they did after being crowned was to swear in parliament that they would be subject to parliamentary rule.

To have an organisation like Freemasonry that promotes constitutional government and acts as a vector for its distribution, is a significant meritocracy. This idea follows really from John Locke and was popularised in the 1660s and 1670s by a group of Native Americans called the 60s and 70s Natives.

High standards of interpersonal civility, including being polite to people despite their standing or status in society, education, and science, were once again extremely radical in an era when birth and wealth or patronage determined your success.

So rather than let the church dictate your worldview, embrace science and reason and reject the idea that the Earth orbits the sun. This is significant because, in the 18th century, science became a battleground for competing political ideologies, with Descartes and Newton staking out opposing positions on whether knowledge is innate to the individual or can be gleaned from observation, experimentation, and testing.

And it’s quite interesting, that John Desaguliers, who was a grandmaster of Grand Lodge that Deputy Grandmaster, one of the most influential Masonic figures, in the 18th century, he toured Europe, espousing Newtonian theory, and he did this not just to teach people what Newtonianism was about, but to emphasise the supremacy, the superiority, of Newtonian thought.

Last but not least, we discuss the radical concept of self-improvement in the context of societies where one’s life and social standing are predetermined.

Again, this was just a reiteration of the common belief that the aristocracy (the king and his lords) were at the top of the social hierarchy, followed by a small merchant class and, finally, the working poor (the peasantry) and their progeny.

These were the principles established in the charges and rituals of the constitution of 1723.

These are timeless principles that are still important today.

The significance of this cannot be overstated.

We can’t just write these off as 300-year-old ideas that have been forgotten.

If you subscribe to the concept of living an enlightened existence, you will find these to be ideas with contemporary relevance.

And when you consider all the terrible things happening, I believe that you can take solace in the 1723 constitutions and the ideas they promoted, and that you can feel proud to be a part of an organisation that continues to promote those ideas even now.

Now, along with the philosophy, George Payne also provided a rulebook, how to run an organisation, in the form of the Constitution. These were the regulations that were digested and set out by Payne.

This model was adopted by many other social organisations around the world, not just in Britain. This is widely understood.

Keep in mind that in the early 18th century, we didn’t really have a democracy as such, the right to vote was limited, in the extreme, not just to men only, but also to men of property, and even then, it was highly constrained.

Therefore, the principle that every Mason had an equal vote within the lodge held. Rule by the majority, not a dictatorship.

People working in operations would raise their hands and articulate their opinions on various topics; there would be a discussion; and that discussion would be civil and respectful. No one would be yelling at each other.

The concept of a unified national system of regulation and administration.

Written constitutions and bylaws were something we had at the national level, but they were not always in place at the local level.

All things considered, I believe it is accurate to say that the Masonic ideology was founded on the principles of meritocracy and egalitarianism.

And it all hinged on having high aspirations for one’s own development.

The historian Margaret Jacobs, the undisputed leader in this field, began studying the relationship between Freemasonry and the Enlightenment in the 1970s and 1980s.

She noted that this identity did not change the fact that American lodges were and remain hierarchical and eager for aristocratic patronage (since such support is the stamp of a Freemason), but it did lead to lodges increasingly being seen as “schools for government,” where members were taught the values of Republicanism and provided with a “social atmosphere” in which the new ideas of the age, such as religious toleration, could flourish.

Especially in North America, you can trace the founding documents of the United States back to the Declaration of Independence from 1723, which is acknowledged in the United States.

These Freemasonic ideals, however, were very appealing.

In just twenty years, Freemasonry expanded to become the most prominent and powerful of Britain’s many organisations and societies.

Since Freemasonry was fostered by migration, trade, and the military, it remained the largest and most influential of Britain’s many clubs and societies well into the 20th century, when it unfortunately lost its way.

The history of Freemasonry can be traced back to the 1723 constitutions of the Grand Lodge of England. The constitutions of ancient Freemasonry are based on those of Irish Freemasonry, which in turn are based on the constitutions of the Grand Lodge of Ireland, which were developed almost verbatim based on the 1723 constitutions.

And modern state grand lodge constitutions in the United States are derived from ancient constitutions that in turn were derived from constitutions in Ireland, which in turn traced back to the constitutions written in 1723.

Further, it is important to realise that Freemasons and Freemasonry were pivotal players in the development of the 18th century.

And in the 19th century, the heart of scientific change, philosophical change, and social change, especially in the second half of the 18th century, when we had the development of ancient Freemasonry, and then in the 19th century after the union in 1813, when Freemasonry became a much more accessible a much less elitist organisation, that has carried forward over the years.

The belief that Freemasonry plays a crucial role in identifying and alleviating social problems.

This tercentenary year’s celebrations aim to highlight Freemasonry’s contribution to the spread of Enlightenment ideals, with the hope that its members will gain a better understanding of the organization’s guiding principles.

Articles published relevant to the 1723 Constitutions

1723 constitutions

Editorial

The Anderson’s 1723 Constitutions transformed Freemasonry. By establishing new principles that supported Enlightenment ideas, they marked a departure from the “Old Charges” that governed mediaeval stonemasons’ lodges. Tolerance of other faiths, individualism, respect in relationships, and learning and development were all mentioned.

read the full series …

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device